Selecting Forage Species

In this module, learn how to choose perennial forage species that are well adapted and productive for your environment based on their forage characteristics and your desired end use.

Key Points:

- Forage species have different yield potentials, growth curves and nutritive values that need to be taken into consideration when choosing a species.

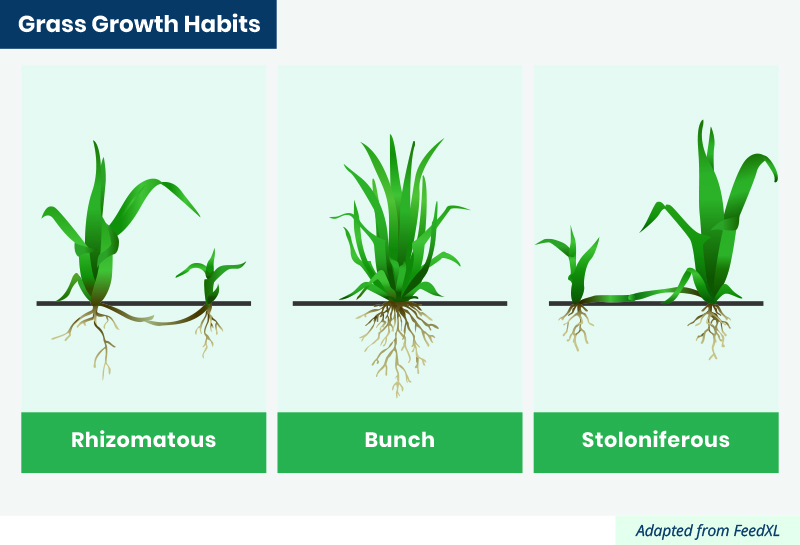

- Grasses are either rhizomatous (sod-forming) or have a bunch type growth form. Rhizomatous species are quite competitive and form dense sod, while bunch grasses leave space between plants making them more suitable for mixtures.

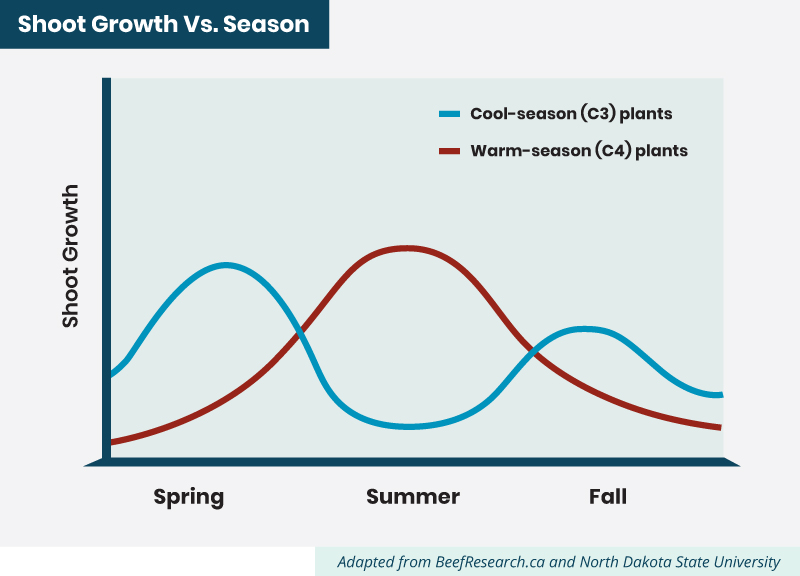

- Cool season grasses initiate growth earlier in the season than warm season grasses but can become dormant during hot and dry summers.

- Legumes have a higher nutritive value than grasses and can increase the pasture productivity when added to a mixture.

- Some legumes have a high bloat risk that can be mitigated through management.

- Legumes tend to have a less rapid decline in digestibility as they mature compared to grasses.

- When properly inoculated, legumes fix atmospheric nitrogen into a form usable by plants.

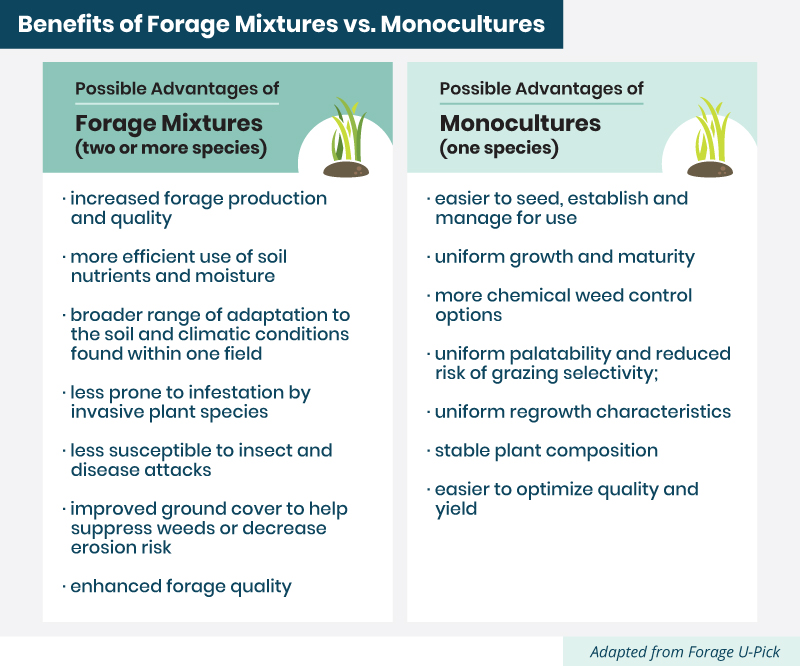

- Single species stands are easier to manage, but mixtures can increase productivity, increase nutritive value and lengthen the season of use.

- When selecting a forage species or mixture take into consideration use of the forage, soil conditions and characteristics, climatic region and stand management.

- Use Forage U-Pick to help you select species well suited for your environmental conditions and intended use.

- Perennial vs. Annual forages

-

Both perennial and annual forages are utilized in Canada for forage production for livestock. Annual plants complete their life cycle in a single growing season and propagate by seed. Annuals must be reseeded each year for a viable forage stand. Perennials persist for more than two growing seasons. Perennials regrow from their roots in the spring and propagate by both tillers and seed.

- Grasses

-

Tillering – when plants produce multiple shoots or stems that branch off from the main stem of the plant

Grasses either have a sod-forming (rhizomatous) or bunch type growth habit. Sod-forming grasses spread by rhizomes (e.g., smooth, meadow, and hybrid bromegrass, creeping red fescue, Kentucky bluegrass) and stolons (e.g., buffalo grass) and form a dense stand, while bunch grasses (e.g., perennial ryegrass, orchardgrass, little bluestem, tall fescue, crested wheatgrass) remain as individual plants that develop clusters of tillers. Rhizomes are modified stems that extend laterally underground, while stolons grow laterally above ground. Both rhizomes and stolons form new, upright stems leading to a dense, sod-like grass stand. In comparison, bunch grasses grow in distinct clumps of vegetation. While the spaces between bunch type grasses can increase risk of weed infestation, bunchgrasses are often very productive as they put a greater proportion of their energy into above ground structures. They grow by tillering at or near the soil surface without rhizomes or stolons, and new biomass grows up from within the plant. Bunch grasses are not overly competitive in forage mixtures than rhizomatous grass species, which makes them a suitable choice for mixtures with legumes.

Grasses are also classified as either warm season (C4) or cool season (C3) plants. Examples of warm season grasses include big and little bluestem, switch grass, side-oats grama, and blue grama. Cool season grasses are species like fescues, bromes, wheatgrasses, and ryegrasses. They have differences in leaf anatomy and enzymes that alter how they carry out photosynthesis. These differences impact their optimal growing conditions, forage quality, nitrogen and water use efficiency, and their seasonal production profile. Cool season plants initiate growth earlier in the spring and grow best between 18°C and 24°C. In warm, dry climates, cool season grasses may go dormant in mid-summer, so are best grazed earlier in the growing season. Cool season grasses tend to be higher in protein than warm season grasses. Warm season grasses experience peak growth in the summer and are better suited for late summer and fall grazing but may not be as well adapted to our Canadian winters.

- Legumes

-

Legumes are forages that have creeping or large tap roots and form seed pods. Both annual and perennial legumes are used as livestock feed and are also recognized for their ability to improve soil. With proper management, legumes can stimulate soil biological activity, improve soil structure, aeration and water-holding ability, reduce erosion and increase organic matter.

Excerpt from BCRC’s Forage Species webpage

Legumes generally have higher protein levels and higher yields than grasses. They also tend to have a less rapid decline in digestibility as they mature. This is related to the leaf to stem ratio of the plant as it matures. The more leaf matter a plant has, the higher quality the forage. Birdsfoot trefoil is an example of a legume species that maintains its forage quality at more advanced stages of maturity because it has thinner stems, maintaining an overall higher leaf to stem ratio.

Some legumes, such as clovers, also have stolons, which contribute to their “creeping” growth pattern. Most legumes also have indeterminant growth, which means that plants continue to grow during flowering, contributing to increased biomass.

Legumes have the ability to fix atmospheric nitrogen into a form usable by plants when properly inoculated.

Some legumes, such as alfalfa, can cause bloat in ruminants. This risk can be mitigated through grazing management and mixed forage stands.

- Forage mixtures

-

When deciding whether to seed a mixture or single species pasture, it is important to take into consideration the intended end use of the forage (pasture, hay, stockpiled), the season of use, and the management of the stand. While single species can be easier to manage, mixtures tend to have higher production and a longer season of use. Species used in a mixture should have complementary characteristics, such as growth pattern, ideal timing of use, maturity, palatability, and longevity.

When grazing a mixture, cattle will choose to graze the most desirable species over less desirable plants. If cattle are allowed to remain in a pasture for an extended period of time or return to a pasture without an adequate rest period, these desirable plants will be regrazed before they have recovered. Over time this will result in the disappearance of these species. Grazing management is integral to the maintenance of any forage stand, whether it is a mixture or a single species.

Species that require an intense graze to prevent heading out and associated decreased palatability issues, like crested wheatgrass or meadow foxtail, are useful for providing pasture early in the season before other species are ready to graze.

More detailed forage species information is available here.

- A tool to help with forage species selection

-

When selecting the species for a forage stand, there are many factors that should be taken into consideration such as end use, management factors, soil characteristics and climatic region.

An interactive forage species selection tool (Forage U-Pick) is available to assist land managers in selecting the correct forage species for their needs. Seeding rate and seed cost calculators, plus information about common weeds and weed management are also integrated within the tool.

To access Forage U-Pick, click the image below

Test Your Knowledge

Adapted from

- Forage Species

Beef Cattle Research Council webpage - Forage Establishment

Beef Cattle Research Council webpage - Forage U-Pick

interactive decision tool - Lacombe Pasture School Proceedings

Western Forage/Beef Group PDF

Other Resources

- New Forage Varieties

Beef Cattle Research Council webinar - Forage Adaptation

Manitoba Agriculture, Food and Rural Initiatives PDF - Alberta Forage Manual

Alberta Agriculture and Forestry PDF