Managing & Planning Grazing

On This Page

GRAZING MANAGEMENT CONCEPTS

PASTURE PLANNING, GRAZING PLANS AND GRAZING SYSTEMS

PASTURE ASSESSMENT

NATIVE RANGELAND MANAGEMENT

Grazing management concepts, pasture planning, grazing plans, grazing systems, pasture assessment and native range management are covered in this module.

Grazing Management Concepts

Key Points:

- Higher stocking densities and shorter graze periods can result in more uniform pasture utilization and manure distribution.

- Stocking density is increased by decreasing paddock size and/or increasing herd size.

- General guidelines for native pasture suggest a utilization rate of 25-50%, and 50-75% for tame pasture. Avoid grazing during sensitive times, such as too early in the spring or when soils in riparian areas are waterlogged.

- To improve management of riparian areas, they can be fenced off so they are able to be managed separately.

- When left on their own, cattle will usually graze unevenly. They will re-graze more desirable plants repeatedly, leading to overutilization.

- Match the class of cattle being grazed to the type, quality, and amounts of forage available as well as land topography.

- Overgrazing is when plants are re-grazed before they have recovered from the previous graze.

- As forage palatability and quality decreases, such as when forages mature, forage intake will also decrease.

- A vigorous forage stand with little to no bare ground will generally be more productive, reduce erosion risks, have an enhanced nutrient and water cycle, and provide stronger competition against less desirable plant species.

- Plants experience rapid growth during Phase II of the growth curve without drawing energy from root reserves and with minimal leaf death. This is usually the optimal time to graze.

- An adequate rest period is necessary for plants to replenish root reserves and regrow.

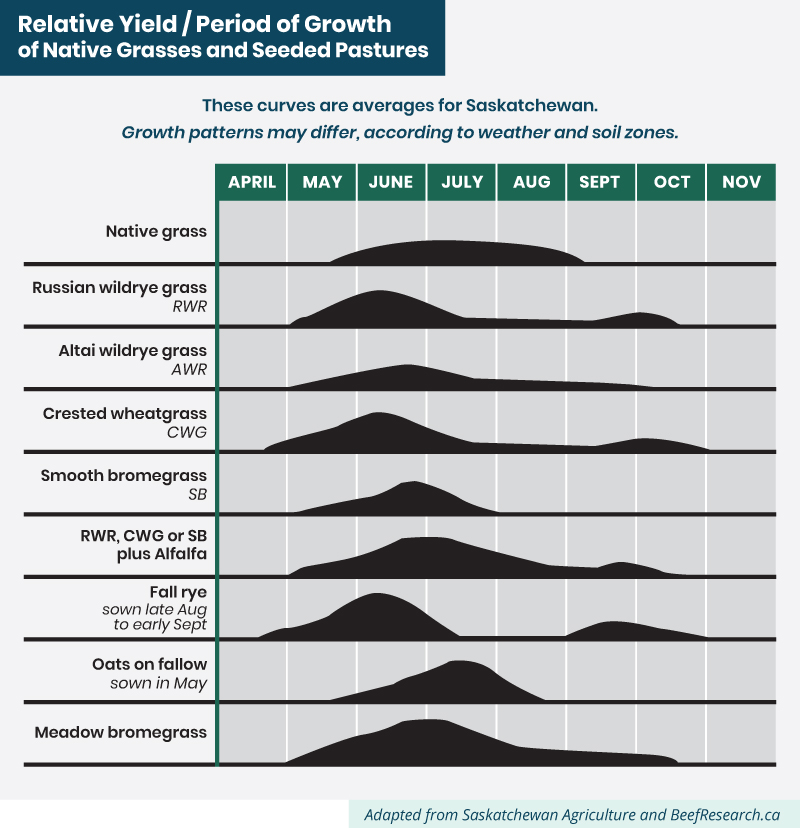

- When plants are growing rapidly (such as in early summer), rest periods can be shorter than when plants are growing more slowly.

- As a rule of thumb, a rest period should be at least six weeks.

- During a drought plants grow at a slower pace. Rest periods should be longer during a drought.

- A drought plan is important so that pastures do not become overgrazed, which can cause forage productivity to fall in subsequent years.

- Balance forage supply and livestock demand. Avoid overstocking a pasture by ensuring there is adequate forage available for the number of cattle, and the length of time, that the cattle will be grazing. General guidelines for native pasture suggest a utilization rate of 25-50%, and 50-75% for tame pasture. These are buffers that allow for adequate rest and regrowth.

- Distribute grazing pressure as evenly as possible across the pasture. When left on their own, cattle will prefer to graze moist, productive areas of a pasture and avoid dry hilltops where the forage quality may be lower. Cattle can be managed to graze a pasture in a relatively uniform manner using a variety of methods depending on forage type, topography, and operational goals.

- Provide rest for pasture plants during the growing season to help plants recover. Forage plants need time to rest to allow them to replenish their energy reserves and prepare for the next grazing event. If plants don’t have adequate time to recover, pasture productivity can dwindle, and pastures can become susceptible to weed infestations, soil erosion and winterkill.

- Avoid grazing during sensitive times. Grazing too early can cause reductions in pasture growth for the whole season. A general rule of thumb is to wait until plants are around eight inches tall, or about the four-leaf stage. Other situations such as species at risk habitat or grazing riparian areas or wetlands may benefit from deferring grazing until nesting season is over or flood potential has subsided.

- Excerpt adapted from the Beef Cattle Research Council’s Grazing Management webpage.

Riparian areas are the lands located adjacent to bodies of water such as lakes, streams, rivers, and wetlands.

- What plants do livestock graze?

-

Cattle usually choose the most desirable plants to graze first and then move on to less palatable plants. If cattle are left in a paddock long enough, they will return repeatedly to those early grazed, desirable plants and graze any regrowth. This weakens these desirable plants because without adequate leaf material for photosynthesis, these plants are unable to restore their root energy reserves. If grazing management is not changed, these desirable plants will begin to disappear from the stand. Rest periods that are too short between grazes can also have the same effect.

As palatability and quality decline, forage intake also decreases. A decline in forage intake often means that the animals are less productive. A decrease in intake can be especially detrimental to classes of cattle with high nutritional needs including calves, backgrounding or finishing yearlings, and cows during peak lactation and breeding.

Select the class of cattle best suited for the kind of forage available and its nutritional quality. For example, dormant forage alone will not meet the high nutrient requirements of cows in late pregnancy or lactation.

Match the class of cattle to your area’s topography. For instance, cows with calves usually will not use steep topography as fully as dry cows or yearlings.

Use the type of cattle accustomed to your environment. For example, cattle raised on flat, open grasslands may need to take some time to adapt when relocated to timbered grazing lands or swampy land.

Consider the animal’s previous grazing experience. Cattle unfamiliar with the kind of plants in a pasture usually will not perform as well as cattle that have previously grazed similar forages.

- What factors affect the productivity of pastures?

-

Plant population

Desirable plant species vary with each pasture or paddock site, type of grazing animal, and the intended use of the forage. It is possible to encourage productive, well-adapted plant species by controlling overgrazing and patch grazing with cross fencing, increasing rest periods during the growing season, varying the timing of grazing, managing soil fertility , or rejuvenating the pasture. To encourage your desired plant population, look at what the desired species key characteristics are and tailor your management to cater to that species. For example, to encourage more alfalfa in a stand, you may consider grazing any grasses in the forage stand a bit more severely to reduce competition.

Plant density

Maximize forage production by maximizing ground covered by productive, adapted forage plants. Less productive plants or weeds compete for light, water and nutrients, limiting overall forage production. Appropriate plant density varies with forage species and environment. For example, bunch grasses will have more bare soil between plants than creeping rooted grasses. Dry environments will have more bare soil between plants than wetter environments.

Plant vigour

Vigourous (larger, healthier, more rapidly growing) plants produce more forage. Plant crowns should have actively growing shoots to provide regrowth after grazing. Vigourous forage plants need to rest and recover from grazing during the growing season. Ensure adequate soil nutrients are available to support forage growth.

Legumes

Legumes, such as alfalfa, sainfoin, cicer milkvetch, clovers, and birdsfoot trefoil, fix nitrogen from the atmosphere and also provide nitrogen to the grasses in the forage stand. Manage pastures to maintain legume populations by ensuring phosphorus, potassium and sulphur requirements are met, selecting long-lived, hardy legume varieties of appropriate species and managing grazing and rest periods to ensure adequate regrowth.

Weeds and brush

Weeds and brush can reduce forage production and restrict livestock access to forage. Managing for vigorous desirable forage plants increases competition and may reduce weed populations. Intensive rotational grazing has been used to reduce weeds and brush. Additionally, herbicides or mechanical methods may be used, in combination with grazing management, to control problem brush and weeds.

For more information, visit the Beef Cattle Research Council’s Weed and Brush Control in Pastures webpage.

Ground cover

Leaving litter (dead and decaying plant material) on the ground improves soil organic matter, the water holding capacity of soil, water infiltration, reduces evaporation, and returns nutrients to the soil. Appropriate litter levels vary by environment, the specific forage site, and the plant species present. For example, bunch grasses will tend to produce less litter than creeping rooted grasses. Litter from productive tame forages in higher rainfall areas breaks down rapidly in the soil. Ground cover can be improved by allowing litter to accumulate.

Soil degradation

Soil degradation, or a decline in soil quality, can be mitigated by reducing the amount of bare soil present. Increasing plant density,vigour, and litter can also reduce soil degradation. Grassing waterways and incorporating buffer zones along streams and rivers generally help to reduce soil erosion. Excessive hoof action on damp, bare soil can result in soil compaction, especially on heavier clay soils, reducing plant growth.

Nutrient cycling

Grazing livestock recycle nutrients through the deposit of manure and urine on the soil that are then utilized for plant growth. To help achieve more uniform distribution of manure across pastures, limit animal congregation near water sources or under trees, and use cross fencing to manage pasture rotations. Ensure soil nitrogen, phophorous, potassium and sulphur levels are adequate by soil testing and addressing any deficiencies through fertilization, manure application or winter feeding on pastures. Ensure nutrients are spread back onto pastures by fencing livestock out of trees, limiting loitering areas near water and cross fencing to get more uniform distribution of manure across pastures.

Grazing pressure and grazing uniformity

Overgrazing reduces forage plant vigour and yield. It can also lead to a reduction in desirable forage species and an increase in less desirable forage species, like weeds. Patchy grazing may result in underutilization of certain areas of a pasture or paddock.. Cross fencing, rotational grazing, and ensuring water is available nearby will help encourage more uniform use.

This information adapted from Alberta Agriculture and Forestry’s Alberta Tame Pasture Scorecard.

- When are pastures most productive?

-

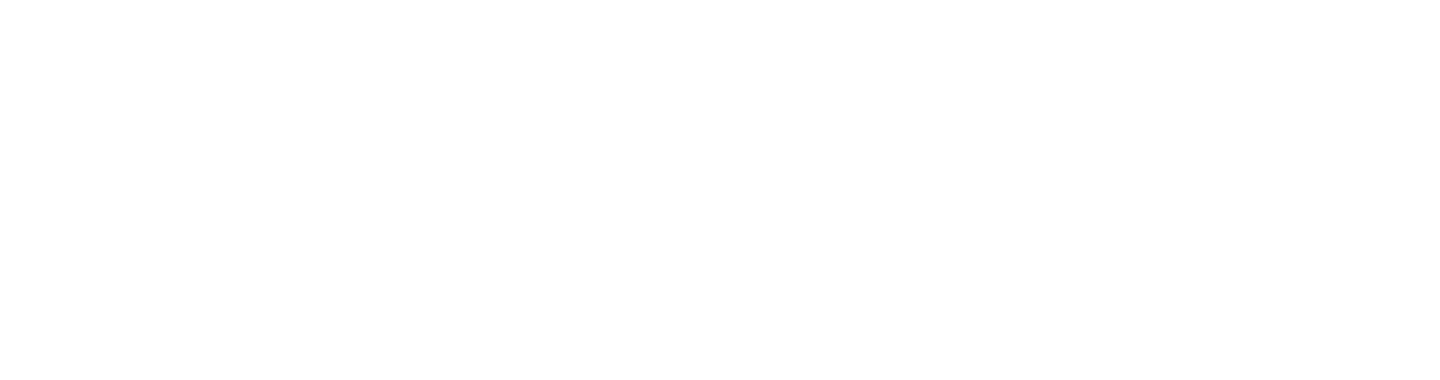

Plants have three phases of growth that form an ‘S’ shaped curve as demonstrated in the figure below. Phase I occurs in the spring following dormancy or after a severe defoliation. During Phase I, the plant draws on root reserves to grow as there is little leaf material to intercept sunlight and gather energy. Phase II occurs when the plant reaches one quarter to one third of the mature plant’s size. The most rapid growth occurs during this phase because there is substantial leaf material to capture sunlight for photosynthesis. During this phase, the plant also replenishes the energy reserves of the root system. Phase III occurs when the plant matures, and new leaf growth is offset by the death of old leaves, flowering, and seed set. Growth slows and generally forage palatability, quality, and digestibility declines.

Productivity is maximized if pastures can be kept in Phase II of growth. This can be achieved by moving cattle into the pasture while plants are in Phase II and removing cattle before the plants are grazed hard enough to return to Phase I. Regrowth will be significantly quicker if plants remain in Phase II and do not have to rely on root reserves for regrowth. Continuously grazed paddocks can result in patchy pasture with a proportion of plants in Phase I or Phase III growth phases. The most desirable plants will be grazed and re-grazed before they are able to recover, remaining in Phase I, with slower regrowth and the potential for loss of desirable plants. Less desirable plants will remain un-grazed and enter Phase III of growth, declining in palatability, quality, and digestibility as they mature.

Increasing the stocking density, limiting the grazing period, and allowing for adequate rest will improve grazing uniformity and help to keep forages in Phase II of growth.

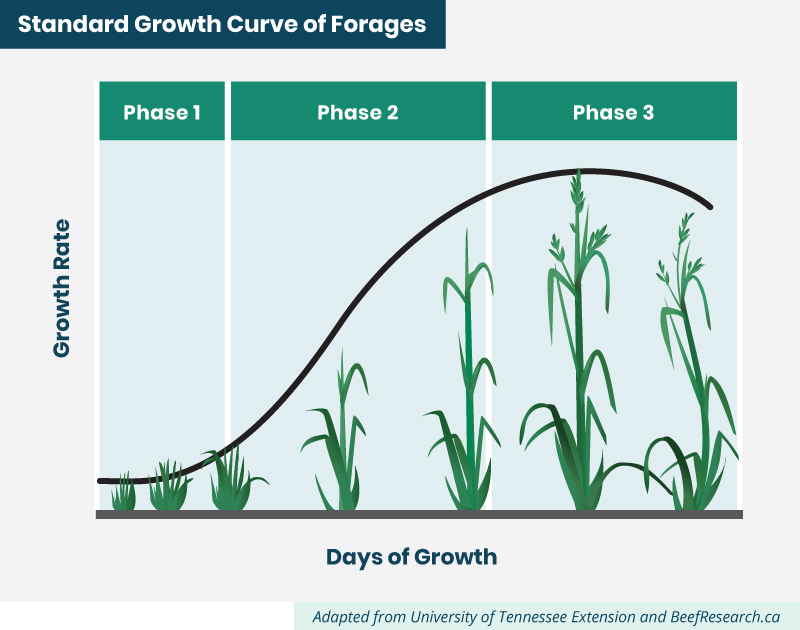

The timing of this growth curve varies between species as illustrated below. Because different forage species will enter Phase II at a different time of the growing season, they should be managed accordingly. When grazing forage mixtures, try to match grazing timing to the growth curve of the most dominant species.

- When should I turn my cattle out on pasture?

-

Tip: Some legumes, such as alfalfa, can cause bloat. Usually, bloat risk is higher risk when plants are immature. For more information on how to mitigate bloat risk, visit the Grazing-Related Animal Health Concerns module.

It is important to delay grazing in the spring until the forage plants have enough above ground growth to replenish their root reserves. For tame pastures this is typically when there is around eight inches of growth, or about the four-leaf stage. For pastures that have a significant amount of legume in the stand, especially alfalfa, it is ideal to delay animal turnout until the plants are at a height of eight to twelve inches. Grazing too early in the season, especially on native rangeland, can be a cause of deteriorating pasture health. Grazing too early will reduce pasture yields throughout the season and can have lasting impacts on forage stand health in subsequent seasons. As a rule of thumb, grazing one day too early in the spring will result in the loss of three days of grazing in the fall.

- How much forage should I let cattle graze?

-

The goal when managing grazing animals is to maximize the amount of forage grazed or utilized without causing lasting damage to the above and below ground growth of desirable forage species. Determining the appropriate level of utilization that is ideal for your grazing situation can take some trial and error, requires adaptability and responsiveness, and relies on animal, environmental, and plant factors.

A general guideline is to “take half, leave half.” This means allowing cattle to graze about 50% of the available forage in the stand. This rule of thumb should be adjusted based on experience and site-specific variables such as forage species, time of year, available forage, and overall management goals. For example, on native rangeland, utilization may vary from 25% to 50%. For tame pasture, you may be able to utilize up to 75% of the available forage. It is important to leave enough leaf material behind so that the plant can continue to capture sunlight for photosynthesis to regrow. The material left behind is referred to as litter or residue and contributes to building organic matter in the soil.

- How does overgrazing occur?

-

Grazing Period – the length of time that livestock are grazing a paddock or certain area of a pasture.

Rest Period – the length of time between two grazing periods on the same paddock

Overgrazing occurs when a plant is re-grazed before it has a chance to recover from the previous grazing event. This can occur if the rest period is too short to allow for sufficient regrowth, or if the cattle are left in the pasture for too long. If the grazing period is too long, cattle will return to graze the fresh regrowth from previously grazed plants instead of grazing the more mature plants in the pasture. Even a single cow left in one pasture too long can result in overgrazing as she repeatedly returns to previously grazed patches.

- What is an adequate rest period?

-

The length of rest that a plant requires following grazing depends on several factors including the type of forage species, plant vigour, the level of utilization, soil moisture, soil fertility, and time of year. When plants are growing more slowly, such as in late summer, recovery times are longer than when plants are growing rapidly in the spring.

A common guideline is that a rest period should be a minimum of six weeks in length.

- How do I achieve uniform grazing utilization?

-

Uniform livestock distribution over the paddock will also lead to more uniform forage utilization and uniform manure distribution, which are two factors that can improve pasture productivity. Grazing distribution varies factors like:

- the type of grazing animal

- topography

- location of water

- salt and mineral placement

- forage species

- forage palatability

- forage quality

- forage quantity

- location of shade and shelter

- fencing patterns

- pasture size

- grazing system

- stocking density

- prevailing winds

Some management techniques to promote more uniform grazing include:

- altering stocking density and/or season of grazing

- forcing animals to specific locations via fencing

- using grazing management strategies such as rotational grazing

- enticing animals to specific locations with water, salt, supplemental feed or rub and oiler placement

- using the type of livestock best suited to the terrain and vegetation characteristics of different grazing areas

- How does stocking density affect pasture health and productivity?

-

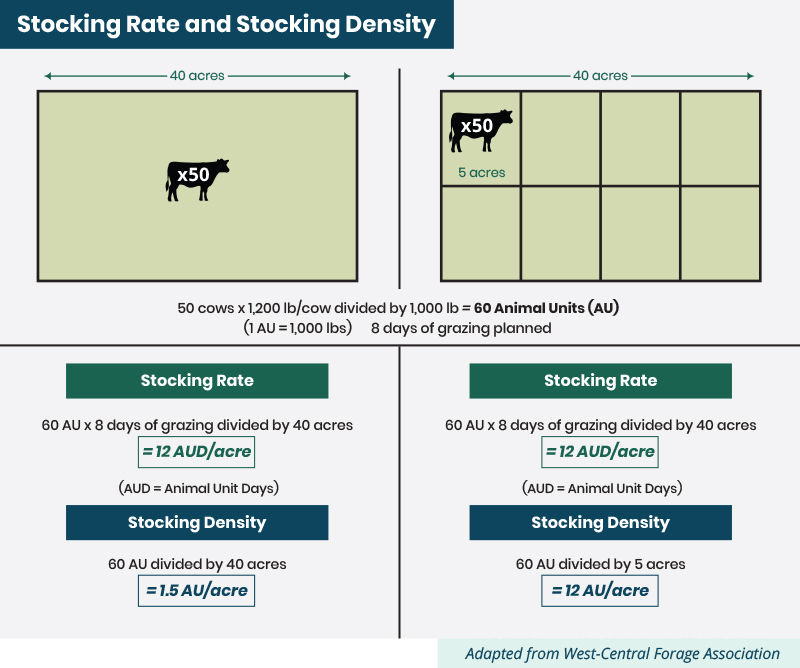

Stocking Rate – the number of animals on a pasture for a given time period, usually expressed as Animal Unit Months (AUM) or Animal Unit Days (AUD) per acre.

Stocking Density – the number of animals per area of pasture, such as a paddock, at any given moment in time, usually expressed as Animal Units (AU) per acre, or pounds of livestock per acre. Stocking density increases as paddock size decreases.

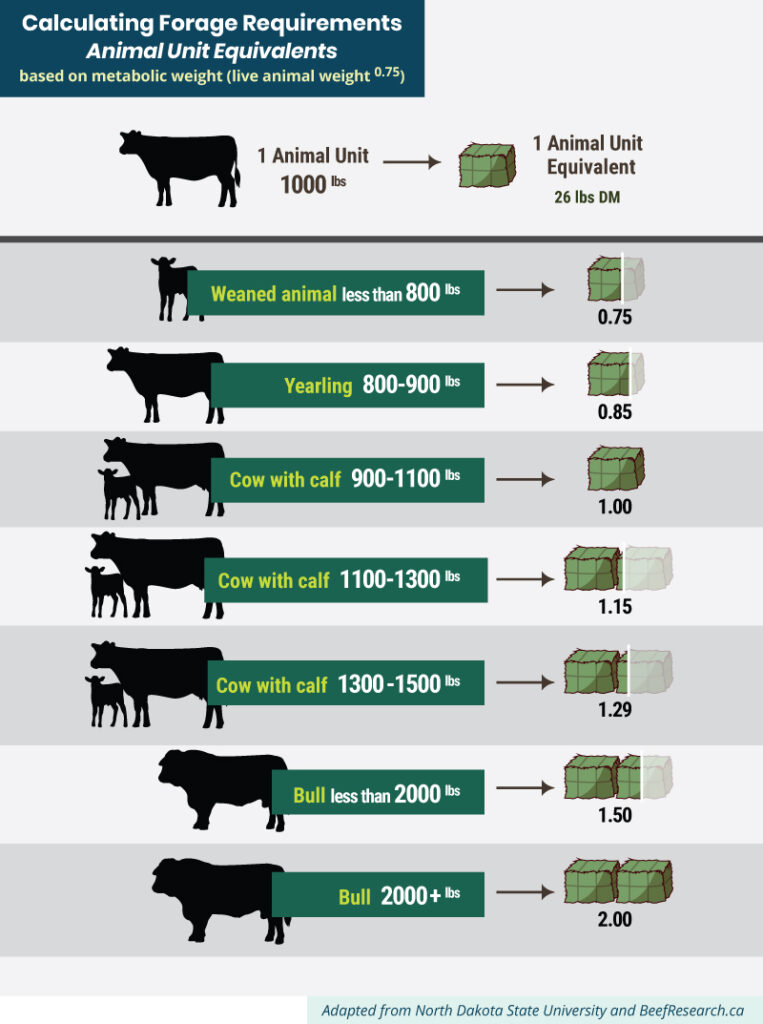

Animal Unit (AU) is a standard unit used in calculating the relative grazing impact of different kinds and classes of livestock. One AU is defined as a 1000 lb (450 kg) beef cow with or without a nursing calf, with a daily dry matter forage requirement of 26 lb (11.8 kg).

Animal Unit Month (AUM) is the amount of forage required to fulfill metabolic requirements for one animal unit for one month (30 days).

Animal Unit Day (AUD) is the amount of forage required to fulfill metabolic requirements for one animal unit for one day.

Animal Unit Equivalent (AUE) is the AU adjusted for different sized animals as not all animals are 1000 lb, and forage requirements change with the size and type of animal.

High stocking density and short grazing periods promote uniform utilization of forage and uniform distribution of manure. This keeps most of the forage plants at roughly the same growth stage, so that the pasture isn’t patchy with some areas of overgrazing and some areas that have been virtually un-grazed. In some situations, such as on pastures or native rangelands that contain species at risk habitat, it may be beneficial to leave some patchy areas in order to support wildlife species.

- How should riparian areas be managed?

-

Riparian areas, such as creeks and streams, can be grazed but access should be controlled during vulnerable times, such as in the spring when stream banks are soft. If possible, riparian areas should be fenced as separate pastures to have more control over potential grazing impacts.

For more information, visit the Beef Cattle Research Council’s Rangeland & Riparian Health webpage.

- How does drought impact grazing management?

-

The benefits of good grazing management practices become more evident in drought conditions. In drought, forage yields can become depleted rapidly, as plants will not regrow quickly without adequate moisture. Planning for drought before it occurs is an important strategy. A drought plan prepared in advance will help you make decisions during a difficult time. It can include any combination of the following strategies:

- Reducing the amount of forage needed by sending cattle to rented pasture outside of the drought zone; supplement available pasture by feeding other forages, alternative, or by-product feeds already on hand either in the pasture or in a dry lot; or downsizing the herd.

- Downsizing can occur in stages such as selling yearlings first, then weaning and selling calves early, before decreasing the number of retained replacements or culling cows.

- Increasing the amount of forage available by purchasing feed; renting additional pasture; seeding unused areas to annual forages for grazing (if the drought is not too severe); and using other annual grain crops for grazing, silaging, or putting up greenfeed.

- A drought plan should include ‘trigger points’ that indicate when alternative actions need to be taken, such as purchasing additional feed or downsizing the herd, etc.

- Trigger points can be based on the amount of precipitation received, or the amount of forage available, and will be unique to your operation.

- For example, if 25% more pasture has been grazed by the end of June compared to a normal year would trigger destocking of the long yearlings, or that additional feed or pasture will be secured.

Adequate litter or residue helps to conserve moisture by shading and insulating the ground, reducing evaporation, and providing forage plants with a more stable moisture source. During a drought, adequate rest periods in a paddock become even more important as plant growth occurs at a slower pace.

Water sources can be limited during a drought. Pastures that have water sources that are at risk of drying up should be grazed first. Both wet well and surface water sources can have heightened total dissolved solids, nitrate, and sulphate levels due to increased evaporation and decreased rainfall. Water quality can change rapidly in these conditions, so it is important to test your water sources more frequently to avoid any potential issues.

Similarly, during a drought when forage is limited and cattle become hungry, they are less selective when grazing. This can cause poisonous plants that would be normally avoided by cattle to be grazed. Moving cattle to new pasture before the availability of desirable forage species becomes too limited can help prevent cattle from grazing any poisonous plants that may be present.

For more information on how water quantity and quality and on how poisonous plants can affect animal health, visit the Grazing-Related Animal Health Concerns module. To learn more about watering systems, visit the Fencing & Water Infrastructure module.

Pasture Planning, Grazing Plans and Grazing Systems

Key Points:

- Implementing a grazing plan along with regular pasture assessments will aid in the overall success of your grazing management.

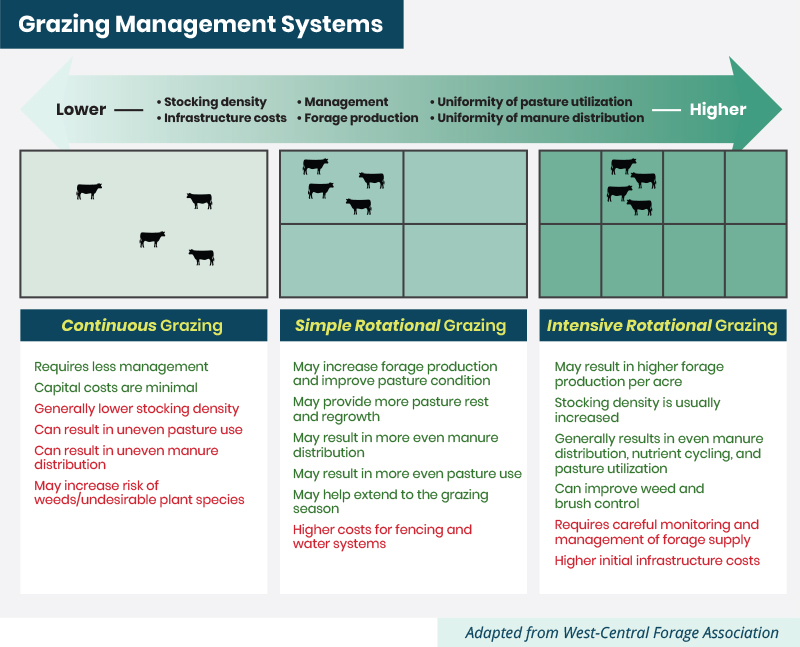

- A goal in all grazing systems is to make grazing management as simple as possible, while still balancing forage supply and demand and optimizing animal productivity.

- The type of grazing system implemented should consider available or desired water and fencing infrastructure.

- Increasing the intensity of a rotational grazing system requires more labour and infrastructure but can also result in higher productivity of both livestock and forage, allow for longer rest periods, encourage more uniform forage utilization, help to suppress undesirable species, and to allow for more uniform manure distribution.

- Continuous grazing systems require the least amount of labour and infrastructure, but may increase the risk of overgrazing, loss of desirable forage species, and the potential for invasion by undesirable plant species.

- A grazing plan should be completed well before spring pasture turnout and match livestock requirements to predicted forage yields as closely as possible.

- Grazing plans should be flexible to accommodate changing conditions such as fluctuations in livestock numbers or drastic swings in precipitation.

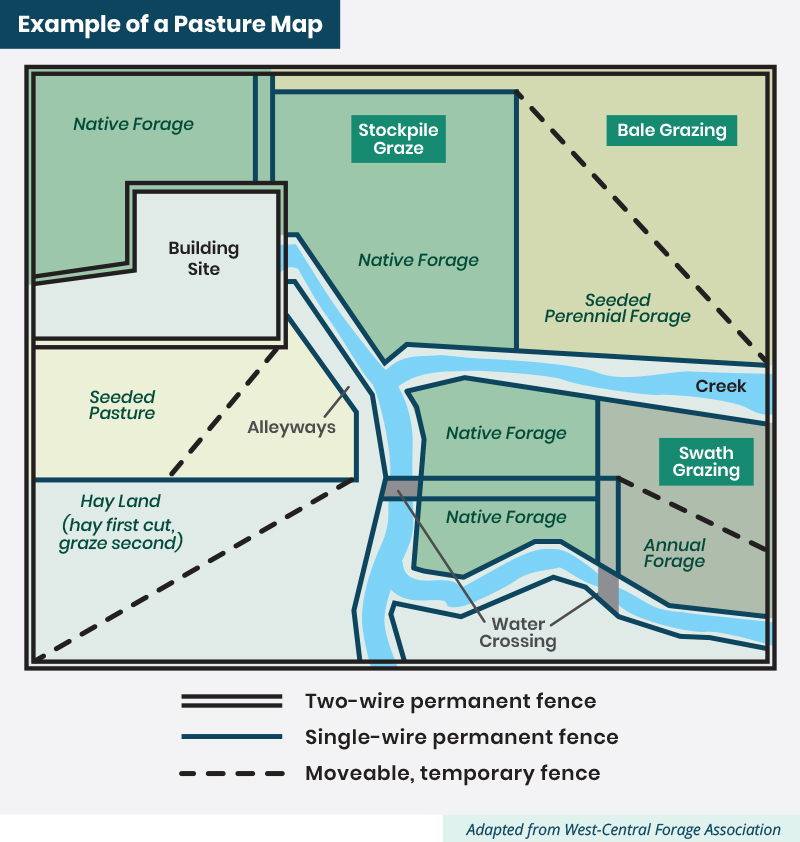

- A pasture map catalogues available resources in different areas and provides a visual planning tool to complement a grazing plan.

- Carrying capacity is the amount of forage available for grazing animals in a specific pasture or field and provides the basis for calculating the number of grazing days available in each paddock

- Carrying capacity can fluctuate throughout the season, as it is affected by animal type, weather conditions, timing of grazing and pasture condition. Be prepared to adjust as the grazing season progresses.

- When dividing pastures into paddocks keep in mind that grazing management is easiest when each paddock contains similar plant species, soil types, and topography. If a single paddock has a large amount of variation in these factors, management is going to be more challenging.

- Use the Number of Paddocks Calculator to determine how many paddocks you may need. An excel version is also available in the Toolkit.

- Accurate, and up to date, pasture records inform future grazing plans by providing an accurate assessment of the carrying capacity of paddocks along with other information such as pasture condition and last graze day.

- There is more to a cow pat than meets the eye. Over 300 insect species can be found in cow dung on Canadian pastures; mating, eating dung, laying eggs, eating each other – all while providing valuable ecosystem services. Learn more in the Cow Patty Critters Guide.

- What are the objectives of a grazing system?

-

When choosing a grazing system, it is important to recognize that objectives that you are trying to achieve by grazing. These are some objectives that are commonly considered:

- Control the pasture areas accessed by cattle.

- Balance forage supply with livestock forage demand. Provide rest and recovery for the forage species.

- Extend the life of the most productive and desirable forage species in the pasture.

- Keep the plants in a vegetative state (Phase II growth phase).

- Improve the nutritional value (quality) of the plants.

- Improve soil quality by growing nitrogen-fixing legumes and recycling nutrients from forage litter and residue.

- Lower the cost of feed by extending the grazing season.

- How do I develop a pasture map?

-

A pasture map is a map of your pasture system that identifies current grazing resources, infrastructure (fencing and water systems) and major landscape features. Use the steps and example presented below to create your own pasture map.

Step 1: Grazing resource inventory

Identify the plant species present and assess the level of management required to maintain the productivity of each species. Include the ideal time during the grazing season that these species will be best utilized. Forage U-Pick can help determine what forage species are best suited for particular times of year. How can you improve the amount of high-quality forages on your land?

Step 2: Map your land

Obtain aerial photographs or sketch out a map of your land. Contact your regional agriculture or county office for aerial photographers in your area or use the Google Earth website. Visit the additional resources at the end of the module for examples of apps that can be used for pasture mapping to assist the development of your grazing management grazing management and pasture mapping.

Step 3: Fill in your pasture map

Label your map with key features that will impact your grazing plan. Features to include on your map are:

- existing or future fence infrastructure

- existing or future watering systems

- seeded (tame) perennial areas

- native forage areas

- annual forage areas

- areas that could be used for either hay or pasture

- dominant plant species and where they are located

- areas that can be used for forage stockpiling

- sensitive lands that are susceptible to wind and water erosion

- ditches, water bodies and riparian areas

- other natural landscape features such as ridges, coulees, draws, treed areas or other wildlife habitat

This information is adapted from the West Central Forage Association’s Pasture Planner.

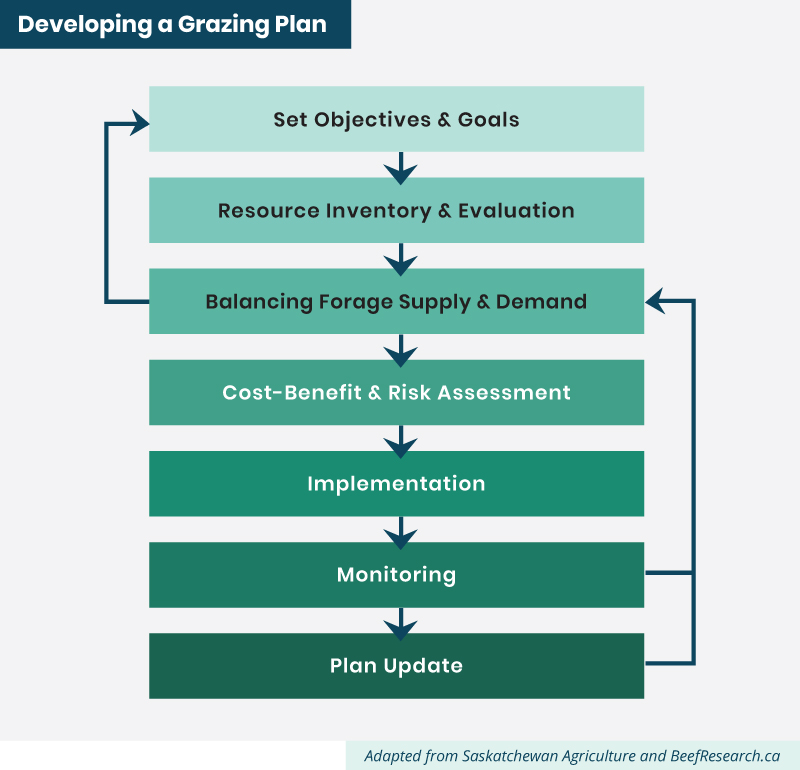

- How do I develop a grazing plan?

-

A grazing plan should be prepared before animal turn out in the spring and match animal numbers to predicted forage yield to promote forage stand longevity and productivity. Defining the goals of the entire grazing system is the first step. These goals can consider:

- Profitability measures.

- Forage productivity measures (e.g., yield and quality).

- Lifestyle choices, including the amount of time spent moving cattle each week and holidays.

- Outcomes such as soil quality, species at risk habitat preservation goals, and ecosystem impact.

- Animal performance.

Remember to account for:

- Available land resources, including rented and owned land, as well as the proximity of cropland to existing pasture systems.

- The quality and fertility of the soil.

- Whether there are sensitive land areas (e.g., erosion prone, riparian area), or other limitations for grazing certain areas of specific pastures or paddocks. Examples include riparian areas, steep slopes, flood prone soils, drought sensitive sandy soils, species at risk habitat, etc.)

- What type of grazing system is the best fit for my operation?

-

A grazing plan can include one or more of these grazing management systems depending on your goals and resources.

Animal Unit (AU) is a standard unit used in calculating the relative grazing impact of different kinds and classes of livestock. One animal unit is defined as a 1000 lb (450 kg) beef cow with or without a nursing calf, with a daily dry matter forage requirement of 26 lb (11.8 kg).

Animal Unit Month (AUM) is the amount of forage required to fulfill metabolic requirements for one animal unit for one month (30 days).

Animal Unit Day (AUD) is the amount of forage required to fulfill metabolic requirements for one animal unit for one day.

Animal Unit Equivalent (AUE) is the AU adjusted for different sized animals as not all animals are 1000 lb and forage requirements change with the size and type of animal.

Stocking Rate is the the number of animals on a pasture for a given time period, usually expressed as Animal Unit Months (AUM) or Animal Unit Days (AUD) per acre.

Stocking Density is the the number of animals per area of pasture, such as a paddock, at any given moment in time, usually expressed as AU per acre, or pounds of livestock per acre. The stocking density increases as paddock size is reduced.

The stocking rate of a pasture can stay constant while the stocking density changes. For example, the stocking density increases as paddock size within a pasture is reduced, as would typically occur in an intensively managed system where the herd is moved multiple times per week or even per day. The stocking rate will stay constant unless the herd size changes or the grazing period for the whole pasture changes.

- How do I know how many days of grazing I can get in a specific

pasture? -

Carrying capacity is the amount of forage available for grazing animals in a specific pasture or field. Having an estimate of the carrying capacity of each of your pastures is important to help establish a grazing plan. Calculating carrying capacity allows you to determine the number of grazing days per pasture. Carrying capacity is affected by animal type, weather conditions, timing of grazing and pasture condition. This means that these calculations are estimates and can change as the grazing season progresses. Be prepared to adjust your grazing plan throughout the season if weather conditions change and use pasture records from previous years to help inform decisions.

The Beef Cattle Research Council’s Carrying Capacity Calculator is a tool designed to help producers estimate how much forage is available for grazing.

Use Method 1 if you wish to calculate an estimate of carrying capacity based on available provincial forage production guides. These estimates are based on projected forage productivity depending on soil type, annual precipitation, and pasture condition. Method 1 works best when the pasture condition (or range health) is similar throughout the field and the forage plant community (or range type) is uniform.

Use Method 2 if you plan on clipping, drying, and weighing samples collected from your pasture. Field-based sampling provides greater accuracy but requires more hands-on work. Producers may choose field-based sampling if provincial guides are unavailable for their region or if pasture types or conditions vary within their field. Forage production varies each year, so the Method 2 approach should include multiple years of sampling to estimate the long-term productivity of the pasture.

In both methods of the calculator, you can input their pasture acreage, animal type (i.e., yearling, cow-calf pairs) as well as forage utilization rate. Recommended utilization rates for native pastures vary from 25-50%. For tame pastures, recommended utilization rates range from 50-75%.

To use the Carrying Capacity Calculator, click the image below.

- How do I calculate stocking rate?

-

When you have a desired herd size:

From Step 4 of the BCRC Carrying Capacity Calculator, enter the grazing days available and the desired herd size in the shaded boxes. The number of grazing days will be auto calculated. An excel version is also available in the Toolkit.

When you have a desired number of grazing days:

From Step 4 of the BCRC Carrying Capacity Calculator, enter the grazing days available. Then enter the desired number of grazing days, and the herd size will be auto calculated. An excel version is also available in the Toolkit.

Tip: For frequent pasture moves and high production pastures, measuring in AUD and Animal Days/Acre provides more accuracy as they are smaller measurement units compared to measuring in AUM and AUM/acre that are better suited for full season calculations and longer pasture stays.

Once you have assessed your forage and pasture resources, decided on a grazing system, and finished your pasture map, you can start building your grazing plan. Use your pasture map and your carrying capacity calculations to decide:

- In which order will each pasture or paddock be grazed?

- At what time of year will each paddock or pasture be grazed?

- How long will each pasture or paddock be grazed?

- How long will the rest period be for each pasture or paddock?

- What type of animal will be grazing each pasture or paddock?

- How many animals will be grazing each pasture or paddock?

- Use the Number of Paddocks Calculator below to help determine how many paddocks you may need. This is also available in an excel version in the Toolkit.

It is important to remember that a grazing plan is not set in stone. Contingency plans are key to a successful grazing season. This includes being flexible with paddock selection, paddock size, the order in which paddocks are grazed, the length of grazing period, and the length of rest periods based upon forage production and weather conditions. Keeping accurate grazing records will help you to adjust your grazing plan throughout the season and in the development of future grazing plans.

- Tips for writing a grazing plan

-

- Utilize your pasture map.

- Avoid grazing an area at the same time of year, every year.

- Avoid grazing pastures when forages are in early (Phase 1) stages of plant growth.

- Rotate pastures more quickly during periods of faster growth and more slowly when growth rates drop.

- How do I divide my pasture into paddocks?

-

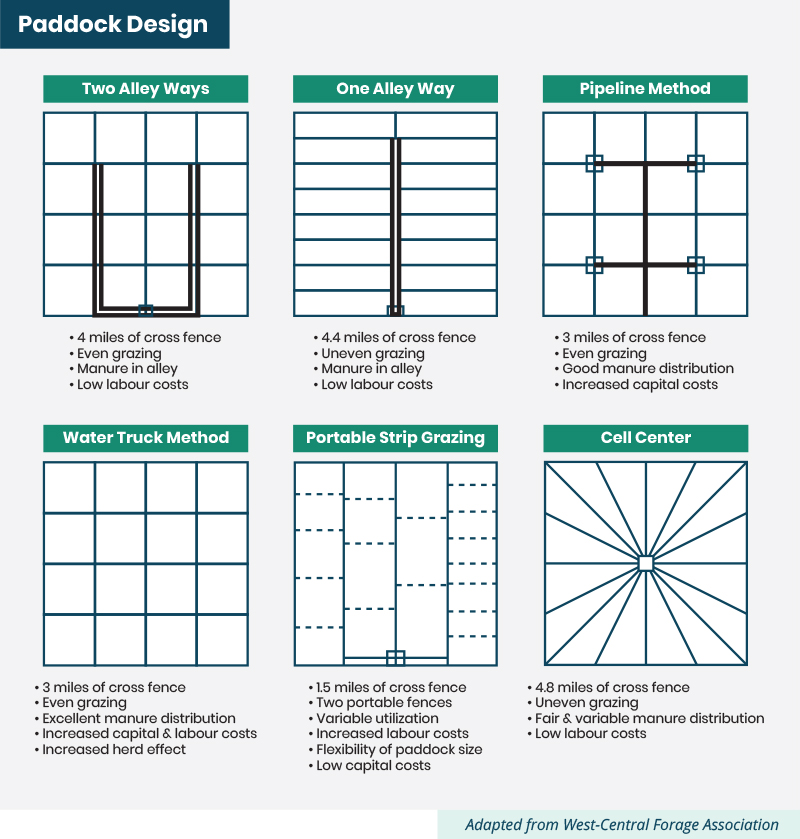

Any grazing system should try to make grazing management as simple as possible while still balancing forage supply and demand and optimizing animal productivity. Management is easiest when each paddock contains similar plant species, soil types, and topography. If a single paddock has a large amount of variation in these factors, management is going to be more challenging.

The Number of Paddocks Calculator can help you determine how many paddocks you may need depending on desired rest period, grazing days, and how many groups of cattle you are grazing. It represents one rotation through each paddock, which may be repeated depending on the length of your grazing season.

Instructions: Enter your desired rest period in days. (If you are unsure of rest period, 42 days is suggested as a reasonable estimate.) Next, enter your desired grazing period in days for each paddock. Then enter the number of groups (e.g., if the cattle are split into 5 separate groups, enter 5; if they remain all together, enter 1.) The number of paddocks needed to accommodate this rotational grazing system will be auto calculated. Here are some tips for planning your paddock layout:

- Fence native or bush pastures apart from tame pastures.

- Fence low-lying areas separately from uplands.

- Fence newly seeded pastures from old forage stands.

- Fence pastures with different forage species separately.

- Fence riparian areas and treed areas separately.

- Avoid designing paddocks that have significant slopes to reduce erosion risk.

- Make paddocks as square as possible to encourage uniform forage utilization and reduce the length of fence needed.

- Fence south facing slopes separately from north facing slopes where possible, because forage grows at different rates on south versus north facing slopes.

- It is more important that the above points are incorporated into paddock design than attempting to ensure that paddocks are all the same size.

Laneways can be used to connect paddocks and connect water sources. Here are some tips for planning laneways in a pasture system:

- Avoid running laneways up and down slopes.

- Avoid running laneways through low or wet areas.

- Place paddock gates in the corner of the paddock nearest to the water source.

- Make laneways wide enough for free movement of vehicles into the paddocks (minimum seven metres wide).

- Make paddock gate widths equal to the laneway width, so the open gate can block access to unnecessary parts of the laneway.

- Consider piping water to paddocks as an alternative to using laneways.

Examples of common paddock and laneway designs are shown below.

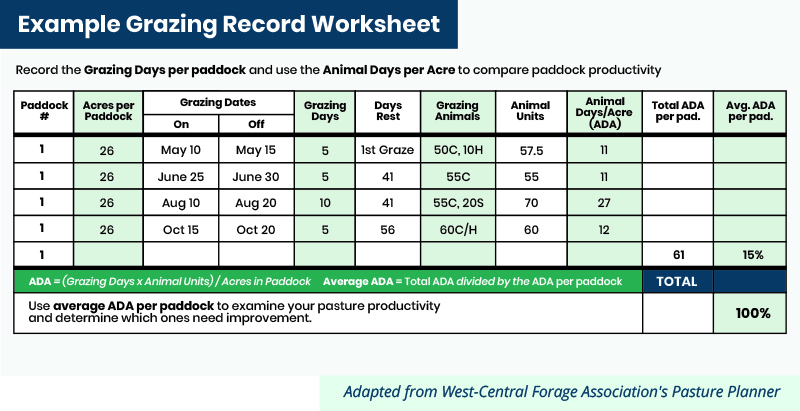

- Keeping pasture and grazing records

-

Keeping records on your pastures and grazing systems will allow for long term evaluation. You can use the results to help inform future grazing decisions. Accurate and up-to-date records allow you to evaluate the past performance of pastures, estimate the carrying capacity of pastures with more accuracy, and establish the forage requirements of your herd. With this information, you can make better management decisions that can positively impact the productivity and health of your pastures and animals. Using your pasture maps, paddock designs, and grazing plans from previous years can also save you some time when planning your grazing system each year because you generally do not have to redraw pasture maps each year and will keep you from inadvertently overutilizing specific pasture or paddock areas.

Blank Grazing Records are available in the Toolkit.

The Beef Cattle Research Council also has a step by step guide to record keeping, including information on keeping grazing and pasture records.

Pasture Assessment

Key Points:

- Pasture assessment is vital to grazing system planning, as this step will help to forecast available forage resources.

- A range of tools exist for pasture and native rangeland assessments in varying levels of detail.

- Choose the level of assessment detail that is reasonable for you to be able to repeat on your pastures on at least an annual basis.

- Regular assessments track pasture health over time. Declines in pasture health indicate a need to change grazing management strategies (i.e., longer rest periods, shorter graze periods, more residue, etc.)

- How do I measure and monitor my pasture health?

-

Many tools have been developed to assess pasture health and they all contain guidelines on how the tools should be used. They can vary in complexity and the scope of information recorded. An example of a more complex assessment tool is the Alberta Range Health Assessment.

Two tools, described below (the Alberta Tame Pasture Scorecard and the Grazing Response Index), are fairly simple to use and have a relatively small time commitment, while still providing useful information to help you make management decisions. These tools are not adequate to perform a full range health assessment on native pastures.

- What is the Alberta Tame Pasture Scorecard?

-

This is a simple, non-technical method to visually assess pastures. It does not require any tools other than a pen and a copy of the scorecard to record your findings. It is both a qualitative and subjective assessment, so it will be most effective when consistently completed by the same person over time, under similar field conditions and at the same time each year. To obtain more accurate results, complete at least three assessments per pasture. More areas of assessment per pasture may be needed if the pasture conditions are very variable from one area to another within the same field.

How do I use the Alberta Tame Pasture Scorecard?

Step 1: Assess pastures during the growing season.

Step 2: Divide the farm or fields into separate sections for assessment based on management practices, soil type or topography.

Step 3: Complete the field identification and management notes section with information regarding the field or area being assessed.

Step 4: Rate each indicator based on your judgement of the pasture and circle the ranking that best describes the pasture condition. For example, when asked for a percentage, make your best visual estimate. Include other indicators that you think would help evaluate your pasture.

Step 5: Follow changes in each of the indicators over time. Note those indicators that need improvement and consider management options that might improve pasture in those areas.

Find the Alberta Tame Pasture Scorecard in the Toolkit.

- What is the Grazing Response Index?

-

The Grazing Response Index (GRI) is an easy-to-use tool to evaluate pastures. It provides a score for each pasture evaluated that can be used to inform management decisions. The GRI can be used on either tame or native pastures. The GRI scores a pasture based on three factors:

- Grazing frequency: the number of times the paddock is grazed in a growing season. If plants are grazed too frequently (before adequate rest and regrowth has occurred) it is detrimental to the pasture health.

- Grazing intensity: the amount of leaf material removed during grazing. Plants rely on the energy produced by photosynthesis or root reserves to regrow. If sufficient leaf material is left after grazing, the plant draws less energy from root reserves.

- Opportunity for regrowth: the length of time the pasture is rested to allow the plants to restore energy reserves and recover from the previous grazing event. The length of the rest period is not a fixed number. It is impacted by the severity of the previous grazing event, the forage species, and environmental conditions, such as temperature, day length and soil moisture.

These three scores will be added together to obtain the overall GRI score for the pasture. It is important to identify whether the pasture is tame or native before beginning the assessment. Native pastures are typically more sensitive to higher grazing intensities than tame pastures, so there are two different GRI calculations to account for this difference.

If the score is positive, this indicates that current management is generally beneficial to plant health, structure, and vigour. If the score is zero, current management is neither beneficial nor harmful, and if the score is negative, it is recommended to look at the factor(s) that may be contributing to declining plant health and make management adjustments as necessary.

The GRI is a short-term assessment tool intended to be used during the current grazing season. It can help inform decisions during the grazing season or potentially for the next grazing season. However, the GRI is not capable of monitoring pasture health, as it does not measure long-term changes on the landscape.

How does the Grazing Response Index work?

Before beginning your assessment, you will need a few tools:

- A place to record days in and days out of pastures (a calendar works well).

- A camera.

- Grazing cages to exclude forages for a visual reference.

- Bookmark this page to use the GRI calculator below or the GRI excel spreadsheet.

Use the GRI calculator to score your pastures. An excel version is also available in the Toolkit.

Native Rangeland Management

Key Points:

- Native rangeland should be fenced separately from tame pastures in order to optimize grazing management.

- Native forages are typically more sensitive to defoliation than tame forages particularly early in the grazing season and during a drought.

- If native pastures are used earlier in the spring, it can be useful to rotate native pastures so that no single pasture sees earlier spring use more than once every five years.

- Many native grasses maintain nutritive quality after they stop actively growing.

- Healthy rangelands provide numerous social, environmental, and economic benefits such as wildlife habitat, forage resources, biodiversity, and carbon sequestration opportunities.

Rangeland, or range, is land supporting native or introduced vegetation that can be grazed and is managed as a natural ecosystem. Rangeland includes grassland, grazeable forestland, shrubland, pastureland and riparian areas.

Excerpt from the Beef Cattle Research Council’s Rangeland and Riparian Health webpage.

- What are the benefits of maintaining healthy, native rangeland?

-

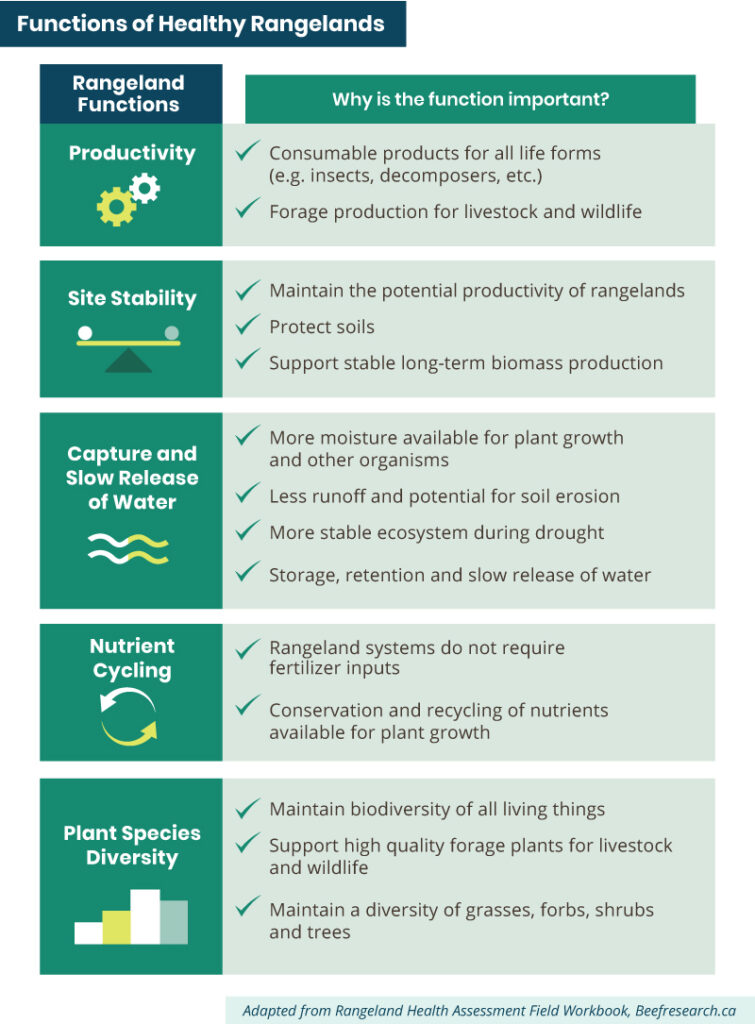

Healthy rangelands provide producers with a valuable forage resource but also provide numerous social, environmental, and economic benefits such as wildlife habitat, biodiversity, and carbon sequestration opportunities. Maintaining healthy rangelands can provide producers with a renewable and reliable source of forage that may be stable during a drought. Healthy native range generally have low noxious and invasive weed populations and can provide quality grazing at different times of year than tame forage species. The following graphic summarizes several of the key functions of healthy rangelands.

- How does management of native rangeland differ from tame pastures?

-

Native forage species are typically more sensitive to defoliation than many tame species, especially early in the growing season and during dry periods. Generally, native pastures are not grazed until mid-summer at the earliest. But regardless of when these pastures are grazed, it is extremely important to manage grazing properly. Ensuring sufficient rest and recovery periods while avoiding severe defoliation will help support healthy and productive rangelands. If native rangelands are used earlier in the spring for calving or other purposes, it is recommended to rotate earlier spring use amongst different pastures, so you avoid using the same pasture at the same time every year. If possible, try to limit earlier spring grazing of a single pasture to only once every five years.

Many native grasses maintain nutritive quality later into the dormant season which makes them superior for late summer, fall, and early winter grazing compared to some of the tame pasture species.

As native rangelands are comprised of very complex and diverse plant communities, management can be much more complex than in a pasture that has only a single or simple mix of plant species.

Plants in native rangelands usually include several types and species of plants, including grasses, legumes, forbs, shrubs, etc. These plants are generally classified based upon how they respond to defoliation as one of:

- Decreasers.

- Increasers.

- Invaders.

Decreasers are species that become less abundant with continued disturbance, such as heavy grazing, because they are typically the most palatable and desirable plants.

Increasers are species that become more abundant under continued disturbance but are typically less palatable and provide less forage than decreaser species.

Invaders are species that are usually considered weeds. They generally establish themselves when more desirable species have died out from heavy or overuse. Invasive plants can decrease biodiversity and rangeland health, reduce forage productivity, increase management costs for control, compromise economic and aesthetic value of the land, and elevate physical, nutritional, and reproductive health concerns within the grazing herd.

Test your knowledge

Information adapted from

- Rangeland and Riparian Health

Beef Cattle Research Council - Grazing Management

Beef Cattle Research Council - Getting Started with Intensive Grazing

Manitoba Agriculture, Food and Rural Initiatives - Drought Management Strategies

Beef Cattle Research Council - Record Keeping and Benchmarking Level III

Beef Cattle Research Council - Grazing Tame Pastures Effectively

Alberta Agriculture and Forestry PDF - Alberta Forage Manual

Alberta Agriculture and Forestry PDF - Grazing Response Index: An Adapted Method for Tame Forages

Saskatchewan Forage Council PDF - Riparian Areas and Grazing Management

Cows and Fish PDF

Toolkit

- Carrying Capacity Calculator

Beef Cattle Research Council - Grazing Record Worksheet PDF

- Alberta Tame Pasture Scorecard PDF

other resources

- Grazing management

-

- Beef Cattle Nutrition

Beef Cattle Research Council webpage - Improving Pasture Productivity: Working with the Weather

Alberta Agriculture and Forestry PDF - Pasture Production

Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs PDF

Plant identification resources:

- Forage U-Pick

- Alberta Forage Manual

Alberta Agriculture and Forestry PDF - Identification Guide for Alberta Invasive Plants

Wheatland County PDF

Examples of pasture planning apps:

- Beef Cattle Nutrition

- Native rangeland management

-

- Rangeland and Riparian Health

Beef Cattle Research Council webpage - Managing Saskatchewan Rangeland

Saskatchewan Ministry of Agriculture PDF

- Rangeland and Riparian Health

- Pasture assessment

-

- Alberta Tame Pasture Scorecard

Alberta Agriculture and Forestry PDF - Grazing Response Index (GRI)

Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada PDF - Rangeland Health Assessment

Alberta Environment and Parks PDF

- Alberta Tame Pasture Scorecard

- Record keeping

-

- Record Keeping and Benchmarking

Beef Cattle Research Council webpage

- Record Keeping for Forage and Grassland Management

Beef Cattle Research Council webinar

- Record Keeping and Benchmarking