Cover Crop Capabilities – Producer and Researcher Experiences

Forage cover crops are annual or biennial plants that farmers seed, often in mixes, in order to “cover” the soil. Also known as cocktail crops or polycrops, producers often seed these blends to accomplish goals like increasing production, reducing evaporation, improving soil biology, providing pollination opportunities, increasing natural nutrient cycling, and providing forage.

As with any practice that gains momentum quickly and offers so much promise, there are some risks and rewards. Read how three producers and one researcher have earned practical experience through trial and error, as well as applied and scientific research. At the end of each profile they share some pointers learned along the way.

Blair Williamson

Lambton Shores, Ontario

Blair Williamson is a purebred beef farmer who has been gaining experience with cover cropping the past few years by working with his uncle. He rents pasture and incorporates cover crops and crop residue before or after traditional cash crops are grown and harvested.

“After winter wheat is taken off in July or August, we plant a cover crop into wheat stubble and either cut and bale or graze that crop,” says Williamson, who adds that they have done this for the last two years with good success. He’s experimented with some different species but has good experience no-till seeding cereal fall rye into soybean stubble, cutting and baling it for feed. “It makes beautiful feed, 18% protein,” Williams says, “but timing of cutting is critical.”

When baling the crop is not feasible, Williamson has been grazing his cattle on the fields, using single-strand portable fencing for strip grazing. He says they feel they’ve seen some soil benefits from cattle activity. “In March and April, we were worried that we had done some hard damage [to the fields] but that turned out to be the best field of corn the past year,” Williamson says.

When it comes to species selection, Williamson has been working with what he knows. “We haven’t been too adventurous, rye works good so we keep sticking with that,” and adds that another common mix is oats and peas with some crimson clover added in. “Moving forward we might try and do something different,” he explains. They have tried inter-seeding which involves seeding a later cover crop into an existing cash crop of corn. While they have had limited success with this practice, Williamson is considering looking at broadcast seeding in the future. “I’m also interested in trying Sudan grass, I think it would work really well in dry conditions after winter wheat, and we could get one cut, if not two cuts off,” Williamson says. “In general, with cover crops, the opportunities are fairly unlimited in what we may do.”

“In general, with cover crops, the opportunities are fairly unlimited in what we may do.”

Blair Williamson

Top Tips

- In order to seed mixtures of species at the proper depth, Williamson tries to find middle ground. “When seeding a mix of peas, crimson clover, and oats, we set the right depth by going with an in between depth for oats and peas,” Williamson said.

- Williamson hears concerns from people about grazing compaction but offers some insight. “We’ve been grazing corn stalks since 2011 and we haven’t seen any soil damage from cattle grazing even if it was a bit wetter,” he says.

Kevin Elmy

Saltcoats, Saskatchewan

Kevin Elmy is an experienced and accomplished cover cropper, and has been experimenting with different species to improve soil health on his family farm, Friendly Acres Seed Farm, since 2009. “We heard about [cover crops] in the U.S. and I thought I would try using tillage radish to see what would happen,” Elmy says. “I started using more diverse blends and here we are today,” he says.

He works to design blends for himself and customers that meet field-specific criteria. “Species selection has to be related to goals,” Elmy maintains. When dealing with fields that have variable topography, such as potholes and hill tops, he says seed blends have to be diverse to reflect these different areas.

Elmy likes a diverse species mix so that some plants are in a vegetative stage at any given time, benefiting soil health. “Vegetative plants feed soil biology through root exudates,” Elmy explains, and adds that producers should consider using a diversity of functional plant groups as well. “Oats, barley, wheat, triticale, rye are all one functional group,” he says. These cereals are often known as cool-season, or C3, species. Producers may also want to add warm-season species (i.e. C4 species), like corn or millet, which flourish later in summer in warm, dry conditions. Other functional groups like broadleaf species, forbs, or legumes, can also be added to the mix. “But first, set goals. It makes species selection and management much easier when you know what you want to do.” Elmy times his seeding operations according to species selection. “Warm-season plants need to have warm soil and warm nights to grow rapidly. Blends high in C4 plants need to be seeded later than C3 plants,” he reasons.

Elmy has also worked with relay cover crops, which is when a cover crop is seeded into a cash crop once the cash crop is established. “I like to give the cash crop a head start then add the relay cover crop. After harvest, the relay crop will continue to grow,” he explains, and adds that producers using relay crops should select low-growing cover crop species or delay seeding so that harvest isn’t impaired. Relay crops are often planted by broadcast seeding or can be added with minimal damage using a disc drill or press drills.

“First, set goals. It makes [plant] species selection and management much easier when you know what you want to do.”

Kevin Elmy

Elmy acknowledges that with cover crops, there may be some bumps in the road, which he refers to as learning opportunities. “Whether it is weather, fertility, or a management oops, things happen,” he says, adding that producers need to evaluate the pros and cons before trying to “fix” a crop. Often, a cover crop can be salvaged, depending on the end goals. “Mowing, grazing, fertilizing, herbicide, or tillage will change how it looks,” he says.

Top tips

- Elmy says weeds are a symptom of a soil problem, in many cases free nitrate in the soil. If producers are planning on using a cover crop for grazing or haying, management may be simple. “Time it so the weeds do not go to seed. It may change your plan, but will fix the problem.”

- Problems with seeding depth can be a common element of failure so to minimize dilemmas, Elmy has a strategy. “We design blends so seed sizes are similar or use species that are forgiving at the wrong depth.”

Brett McRae

Brandon, Manitoba

Brett McRae operates McRae Land and Livestock near Brandon, Manitoba, where he sells purebred cattle, runs yearlings, and seeds both cash and cover crops. He has been seeding cover crops for about five years with the aim of keeping the living root of the plant growing as long as possible. “Cover crops fit in with soil health, give me feed, animal integration, everything fits together and checks a lot of boxes,” McRae says.

McRae has experimented with many different species. He’s planted mixes including brassicas, fall and winter cereals, Italian rye, crimson clover, spring cereals, corn, hairy vetch, buckwheat, millet, red clover, and more. McRae’s had some hits but some misses as well. “I can’t use brassicas because we have really high sulphur soils and ran into sulphate toxicity,” he says. “When you look at your natural species around you and use that as a guide, things tend to work a lot better,” he says. “Now basically when I’m picking species, I’ll take something that I know works for sure then add in things that I hope will work.”

McRae has experimented with timing of seeding as well as seeding method. “In the past year, I seeded every Friday for five weeks to find my ideal seeding date, and they all worked,” he said. He will often seed a cover crop after harvesting a winter wheat or pea crop, however dry conditions in late summer may not allow the crop to germinate until fall rains arrive. He used to broadcast seed and rely on combine residue to cover seeds and while it’s a convenient method, success was not consistent. “If we were in a wetter environment, maybe like irrigation, it would be a no brainer, but seed to soil contact is very important.”

“When you look at your natural species around you and use that as a guide, things tend to work a lot better.”

Brett McRae

McRae has gotten inventive and builds and modifies his equipment as he needs to. “This past year I built an inter-seeder so I could seed between the corn rows,” he says, adding that he prefers inter-seeding cover crops (similar to relay cropping) to take advantage of weed control. He can perform an in-crop herbicide application in his cash crop of corn, wheat, canola, or oats, then inter-seed a secondary cover crop. The cover crop germinates and once the cash crop is harvested and the canopy is open, the cover crop takes over.

McRae says observation is key. “We are all learning this together, no one has all the answers yet,” he says. “In my trials, I design it so I can plan for something to go wrong,” he says and adds that every experience leads to an opportunity for improvement. “What can I learn from this to tweak for next year?”

Top tips

- If producers are using cover crops as a method to eliminate using herbicides or crop inputs, it’s better to transition slowly. “You can’t just quit fertilizer and crop inputs cold turkey, there’s a reason why we use those products,” he says. “It doesn’t necessarily have to be a slow transition but a smart transition away from inputs if that’s what you want to do,” he suggests.

- Be cost conscious. “Don’t spend too much money doing this. Whether it’s equipment or seed, there are a lot of people in the marketplace that will try and sell you a lot of different things, but they may or may not fit what you are doing,” he says. “You will need to invest something but don’t go overboard,” he says, adding that in many cases producers can use what equipment they already have on hand.

Jillian Bainard, PhD

Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada

Swift Current Research and Development Centre, Saskatchewan

Jillian Bainard, PhD, is a research scientist who is working to understand how forage cover crops grow in semi-arid Saskatchewan. She’s looking at whether these crops do what they are professed to do, including studying whether they improve soil in a measurable way, and whether producers can reduce inputs through cover cropping. Bainard presented her work during a recent BCRC webinar.

She has many ongoing projects including a collaborative study evaluating the impact that cattle have when they are introduced into a forage cover crop. She’s studying the potential impact that cattle manure and urea has on soil fertility as well as whether trampling or compaction has a positive or negative affect on various soil physical characteristics. The study also has an economic component as it investigates integrated crop-livestock systems.

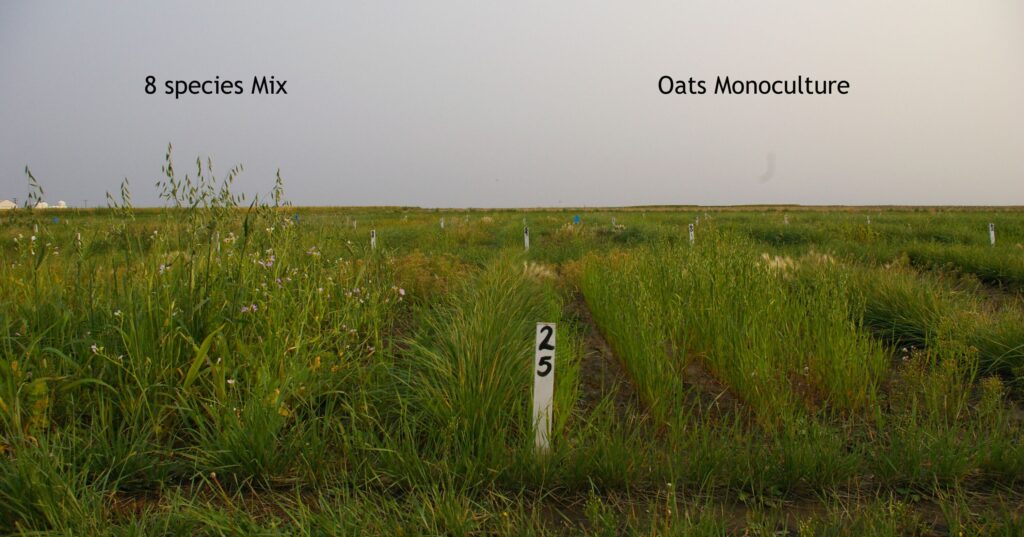

When asked about species selection, she says it can vary depending on how much time and effort producers want to put into seeding a crop. A labour-intensive solution might be to seed different crops in different zones of varying topography or soils, however a mixture is more practical. “The goal of a more diverse crop mix is that a farmer might have more of a buffer against crop failure in difficult areas,” she says.

Seeding a mix of crops with a variety of seed sizes can be difficult because different plant species should be seeded at different depths. “Seeding options will depend on the type of equipment at your disposal,” Bainard says. “Some farmers use the fertilizer side-bander to seed at different depths – run the smaller seeds together at a shallow depth and the larger seeds together at a deeper setting,” she explains. “Another option is to do multiple passes, although obviously this is a nuisance,” Bainard says. “I have also seen some interesting “homemade” equipment built for intercropping,” she notes.

For most of her research trials, different seeding options were not feasible. “We seed everything together in a combined mix at an intermediate depth of around three quarters of an inch to one inch deep (2-2.5cm),” she says. “This is a bit shallow for the large-seeded crops, and a bit deep for the small-seeded crops, but we’ve had pretty good success at getting everything to grow,” she explains.

Establishing a cover crop is largely weather dependent and needs to balance out the end use. “You’ll be looking for good soil moisture, but of course you need to consider your end goal. If you want late-season forage, seeding later will be a good option,” she says. “For famers that want to graze a cover crops, they would have to anticipate when the crops will be at peak biomass and where this fits into their grazing rotation,” she adds.

Bainard has had mixed experiences with weeds and forage cover crops. “In some trials, I have documented weed reduction in the mixture plots compared with the monocultures,” she says. “I have also seen what happens when forage cover crops do not establish well and get overrun by weeds,” she explains, adding that herbicide control is usually not an option because most mixes have both broad leaf and cereal species. “I think there is a lot of promise for using crops like brassicas to help control weeds,” Bainard says, adding that brassicas have strong above-ground competition. They also have the potential for allelopathy, which means their root system potentially gives off toxins that inhibit other plant growth.

Top tips

- Producers may want to start by choosing a simple mix likely to grow well in their region. “Picking a mix that is moderate in the number of species and complexity will reduce the amount of potential issues and trouble-shooting that you might have to do,” she adds.

- Caution is advised with potential cover crop species that could become weedy. “For example, hairy vetch is often labelled as an annual, but can act more like a biennial and will re-grow the following year,” Bainard says. This may lead to an unwanted situation in the future.

- Bainard says it’s helpful to be adaptable. “If something isn’t working, be ready to use the cover crop in a way you weren’t necessarily intending to – maybe instead of grazing a crop you have to bale it, or maybe you can’t use it for feed and have to treat it as a plough-down, and hope that there are other benefits for your soil in the long run,” she says.

Producers and scientists alike are still navigating when and how to incorporate cover crops in real world situations. There are many considerations with cover crops, from species selection to how to get the seed in the ground, however the practice shows great potential and is making a big impact on many farms across Canada.

Learn More

- Assessing the impact of grazing annual forage cover crops in an integrated crop-livestock system (BCRC Research Fact Sheet)

- Cover Crops (BCRC web page)

- Cover Crops are a Balance Between Reward and Risk (BCRC blog post)

Click here to subscribe to the BCRC Blog and receive email notifications when new content is posted.

The sharing or reprinting of BCRC Blog articles is welcome and encouraged. Please provide acknowledgement to the Beef Cattle Research Council, list the website address, www.BeefResearch.ca, and let us know you chose to share the article by emailing us at info@beefresearch.ca.

We welcome your questions, comments and suggestions. Contact us directly or generate public discussion by posting your thoughts below.