Pourquoi cette boîterie ? Analyser le problème chez les bovins 🎙️

CLIQUEZ SUR LE BOUTON « PLAY » POUR ÉCOUTER CET ÉPISODE (article offert en anglais seulement):

Écoutez d’autres épisodes sur BeefResearch.ca, Spotify, Apple Podcasts, Amazon Music ou Podbean.

Cet article rédigé par le Dr Reynold Bergen, directeur scientifique du BCRC, a été initialement publié dans le numéro de octobre 2024 du magazine Canadian Cattlemen et est reproduit sur BeefResearch.ca avec la permission de l’éditeur.

Les bovins boitent pour de nombreuses raisons, notamment en raison de blessures, d’une mauvaise conformation, d’une surcharge en céréales, de mycotoxines (par exemple, l’ergot) et d’une infection bactérienne. Les différents types de boiteries doivent être traités différemment. Un traitement antibiotique n’est utile qu’en cas d’infection bactérienne.

La boiterie est la deuxième raison (après la maladie respiratoire bovine) pour laquelle les bovins des parcs d’engraissement sont retirés et reçoivent des antibiotiques. Les bovins boiteux mangent moins, grandissent plus lentement et moins efficacement, peuvent être expédiés plus tôt et ne sont souvent pas aussi bien classés. Ces facteurs représentent un coût économique important. Lorsque les bovins boitent à la fin de la période d’alimentation, les délais d’attente avant l’abattage limitent le nombre d’options de traitement antibiotique.

Une équipe de chercheurs canadiens dirigée par Karen Schwartzkopf-Genswein, d’Agriculture et Agroalimentaire Canada, a récemment publié une revue des études à grande échelle sur la boiterie chez les bovins en parc d’engraissement (A Review of Foot Related Lameness in Feedlot Cattle; https://doi.org/10.1139/cjas-2024-0047).

Ce qu’ils ont fait

Ces chercheurs ont passé en revue les études portant sur les boiteries infectieuses du pied (à l’exclusion de l’arthrite chronique liée au mycoplasme ou à l’histophilus) chez les bovins en parc d’engraissement. Il s’agissait de plusieurs études pluriannuelles menées dans des parcs d’engraissement canadiens, avec des dossiers de traitement portant sur 10 000 à plus de 1 000 000 de bovins. Des détails importants et difficiles à trouver peuvent apparaître lorsque les chercheurs disposent d’ensembles de données très volumineux.

Ce qu’ils ont appris

Le piétin est la cause la plus fréquente de boiterie infectieuse du pied dans les parcs d’engraissement. Il peut survenir à n’importe quel moment de la période d’engraissement (ainsi que dans les exploitations vache-veau). Le piétin provoque un gonflement entre les griffes du sabot (souvent sur le membre postérieur) qui peut s’étendre à la partie inférieure de la jambe. Si l’avant du pied est propre, une lésion de piétin a souvent un aspect sombre et est entourée de bords déchiquetés où la peau se détache. Une détection et un traitement précoces sont essentiels pour éviter une aggravation de l’infection. Le piétin répond généralement à n’importe quel antibiotique à action prolongée. Si le traitement initial ne fonctionne pas, il ne s’agit probablement pas d’un piétin. Plusieurs bactéries différentes semblent être impliquées, ce qui pourrait expliquer l’inefficacité des vaccins disponibles contre le piétin. Le piétin est plus fréquent dans les enclos en mauvais état ; un bon drainage et une bonne litière contribuent à réduire le risque.

La dermatite digitale (également connue sous le nom de DD, pourriture du pied de la fraise, verrue poilue du talon) est généralement beaucoup moins fréquente que le piétin chez les bovins en parc d’engraissement. La dermatite digitale est plus souvent associée aux vaches laitières. La dermatite digitale est rarement diagnostiquée dans les exploitations vache-veau, mais elle est de plus en plus fréquente dans les parcs d’engraissement. Elle n’apparaît généralement pas avant que les bovins n’aient été nourris pendant trois mois ou plus et peut être associée au piétin. Les bovins atteints peuvent ne pas boiter et le pied atteint peut ne pas être enflé, de sorte que ces bovins peuvent être plus difficiles à trouver dans l’enclos (ce qui peut expliquer pourquoi la dermatite digitale n’est pas souvent observée ou diagnostiquée dans les exploitations vache-veau). La dermatite digitale se manifeste d’abord par une lésion circulaire ou ovale de couleur rouge fraise à l’endroit où la peau et le bulbe du talon se rejoignent à l’arrière du pied. Dans le cas de lésions plus avancées ou chroniques, la peau infectée peut devenir rugueuse, écailleuse et présenter de longues lésions ressemblant à des longs poils fibreux. La dermatite atopique réagit généralement aux antibiotiques topiques tels que la tétracycline. Les bains de pieds à base de sulfate de cuivre sont moins efficaces, surtout lorsqu’ils sont contaminés par des sabots sales. L’élimination correcte du sulfate de cuivre usagé est également un problème. La dermatite digitale est causée par de multiples bactéries, mais des bactéries différentes de celles du piétin. Il n’existe pas de vaccin. Un enclos propre, bien drainé et doté d’une bonne litière contribue à réduire le risque. Les bactéries de la dermatite digitale peuvent survivre dans le sol et infecter de nouveaux bovins, de sorte qu’une fois qu’un parc d’engraissement est contaminé, cela devient probablement une réalité.

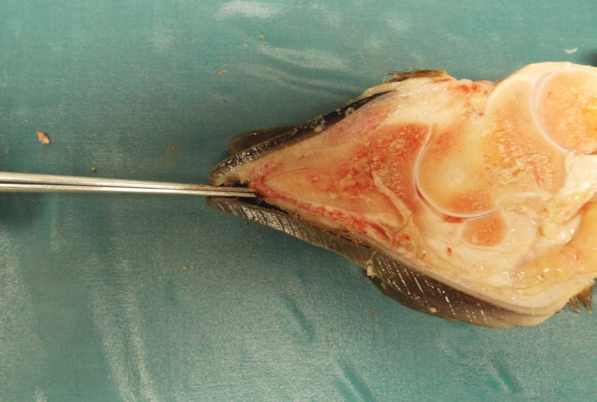

La nécrose de la pointe des sabots survient presque toujours dans les premiers jours ou les premières semaines suivant l’arrivée des bovins au parc d’engraissement. Elle se produit toujours dans l’un ou les deux membres postérieurs. Il n’y a pas de gonflement, ce qui la distingue du piétin et des traumatismes. On pense qu’elle survient lorsque la plante d’un pied postérieur a été éraflée sur les

sols en béton rugueux à l’encan ou dans l’aire de manutention. La plante usée peut alors développer une minuscule fissure à l’endroit où elle rencontre

l’orteil du sabot. Cette fissure permet aux débris et aux bactéries de pénétrer (un peu comme une fente sous l’ongle) et de déclencher une infection. La maladie est plus fréquente chez les bovins excitables et dans les groupes qui sont manipulés de manière agressive. Au début de la maladie, les animaux affectés ont tendance à boiter légèrement et à faire des pas très courts. Toutefois, en l’absence de traitement, ces animaux peuvent devenir boiteux à trois pattes.

Le diagnostic et le traitement consistent à pincer le bout du sabot pour confirmer le diagnostic, à le laisser s’écouler comme un abcès et à administrer un antibiotique à action prolongée. Les meilleures préventions consistent à éviter la tentation d’acheter des bovins sauvages à un prix avantageux, à avoir des sols rainurés de manière appropriée (et non agressive) dans les zones de manipulation et à manipuler les bovins avec un minimum de stress.

En bref

Toutes les boiteries ne sont pas causées par une infection et tous les bovins boiteux n’ont donc pas besoin d’antibiotiques. Toutes les boiteries ne sont pas dues au piétin, il n’existe donc pas de traitement unique. Il est beaucoup plus facile de prendre une décision de traitement appropriée si vous pouvez bien examiner la patte avant de la traiter, afin d’être plus sûr des raisons de la boiterie et de la façon de la traiter de manière appropriée.

Alors, qu’est-ce que ça signifie… pour vous?

La manipulation des bovins à faible stress et le maintien des enclos aussi propres et secs que possible ne sont pas toujours faciles ou bon marché, mais la boiterie non plus.

Le Conseil de recherche sur les bovins de boucherie est une organisation sans but lucratif financée par le Prélèvement national sur les bovins de boucherie. Le BCRC s’associe à Agriculture et Agroalimentaire Canada, aux groupes provinciaux de l’industrie du bœuf et aux gouvernements pour faire progresser la recherche et le transfert de technologie à l’appui de la vision de l’Industrie canadienne du bœuf qui consiste à être reconnue comme un fournisseur privilégié de bœuf, de bovins et de génétique sains et de haute qualité. Pour en savoir plus sur le BCRC, consultez le site suivant : www.beefresearch.ca.

Le partage ou la réimpression des articles du www.BeefResearch.ca est généralement bienvenu et encouragé, mais cet article nécessite l’autorisation de l’éditeur d’origine.

Vos questions, commentaires et suggestions sont les bienvenus. Contactez-nous directement ou suscitez un dialogue public en publiant vos réflexions ci-dessous.