Genes Behind the Scenes 🎙️

This article written by Dr. Reynold Bergen, BCRC Science Director, originally appeared in the August 2024 issue of Canadian Cattlemen magazine and is reprinted on the BCRC Blog with permission of the publisher.

CLICK THE PLAY BUTTON TO LISTEN TO THIS POST:

Listen to more episodes on BeefResearch.ca, Spotify, Apple Podcasts, Amazon Music or Podbean.

The cattle you raise and the beef they produce are the result of two factors – their genetic potential, and the environment they’re raised in (climate, feed, health management, handling practices and everything else you do).

The beef industry adopts genetics more slowly than poultry, swine or dairy. Several things make genetic advancement trickier in beef cattle.

Comparing beef to other industries is like comparing apples to oak trees – our production systems are very different. Pigs, poultry and dairy cows are usually raised in intensive confinement systems that tightly control the physical environment and diet. This means production practices (and productivity) can be reasonably similar across the entire country. When a barn largely eliminates the environmental factors, even the most demanding genetics can be accommodated. In contrast, cow-calf production takes place in the natural environment. Beef cows need all the genetic flexibility they can get to cope with blizzards, drought, bogs, hills, parasites, predators, highly variable feed quality and availability, and everything else nature throws at them. Genetics that can’t cope with those conditions tend to drop out in these situations. The feedlot sector is more intensive and could likely get more out of those genetics.

Our marketing systems are also like apples and tumbleweeds. With pigs, poultry and dairy, the producer who decides (or is instructed) what genetics to use also sells the eggs, milk or slaughter-ready bird or pig. Their customer provides a clear economic incentive for product quality. Cow-calf producers who don’t retain ownership are paid for weaning weight, and are incentivized to maintain fertility and longevity. Focusing too much on better feedlot performance, feed efficiency or carcass merit genetics could lead to a tradeoff in fertility or longevity. Feedlot producers would undoubtedly love to see higher efficiency, growth and carcass quality genetics. But they rarely produce their own calves and only buy a fraction of their calves directly from the farm. So, the feedlot sector works the “environment” side of the equation by sorting weaned calves into finishing, backgrounding, or grass yearling systems based on sex, weight and breed-type, and tailor their diet and management to get the most out of the genetics they think they bought.

But the genetic quality of Canada’s beef cattle is improving behind the scenes. Most cow-calf buyers may not be deliberately seeking improved genetics for growth or carcass quality. But if they’re buying yearling bulls from breeders who are selecting for those traits, then those improved genetics are feeding into the whole system.

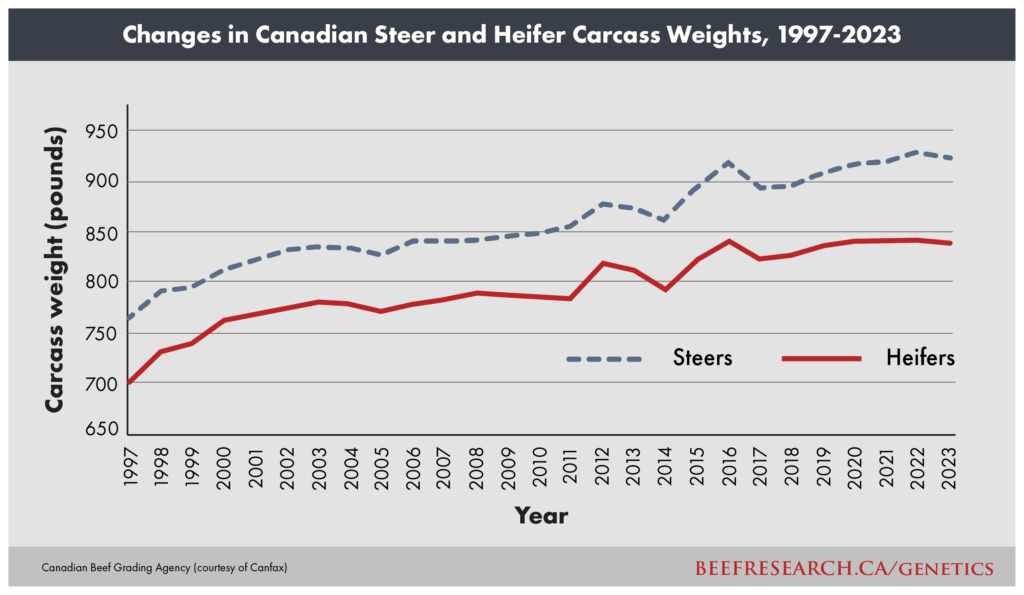

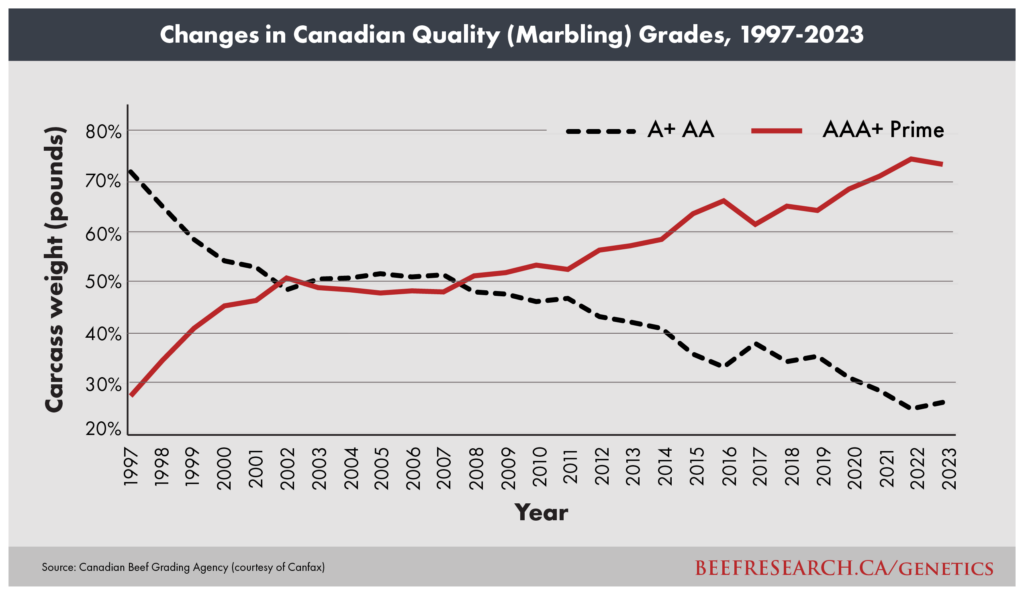

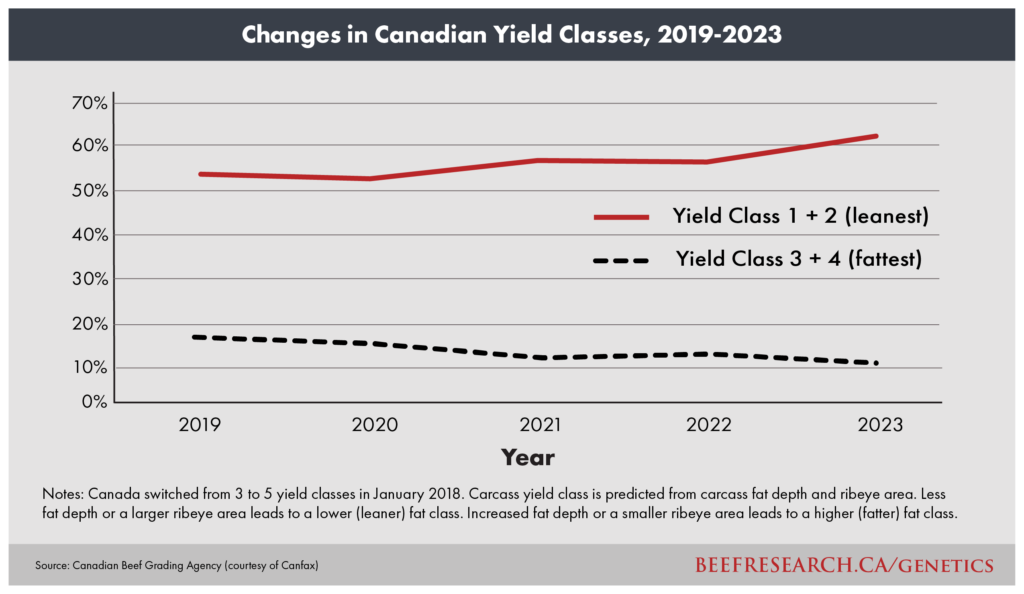

Here’s the evidence. After ignoring marbling for decades, Canada adopted the U.S. marbling standards in 1996. Between 1997 and 2023, the percent of youthful Canadian beef carcasses falling into the lowest two quality grades (A and AA marbling) dropped from 72% to 26%, while the two highest quality grades (AAA and Prime) rose from 28% to 74%. Carcass quality is improving. So is growth. Over the same period, average carcass weights for steers and heifers increased by 5.5 and 4.4 pounds per year. These increases add up. By 2023, steer and heifer carcasses weighed 20% more than they did in 1997. As an aside, that’s partly why beef supply hasn’t dropped as fast as cow numbers – each carcass produces more beef. Producing more beef from each animal has also played a major role in helping shrink the environmental footprint of Canada’s beef industry.

Make no mistake – improved quality grades and carcass weights were due to a lot of things, including packer premiums for quality grade, smaller penalties for heavy carcasses, longer days on feed, changes in breed composition (including the recent adoption of beef on dairy crosses), growth promotants and feeding practices.

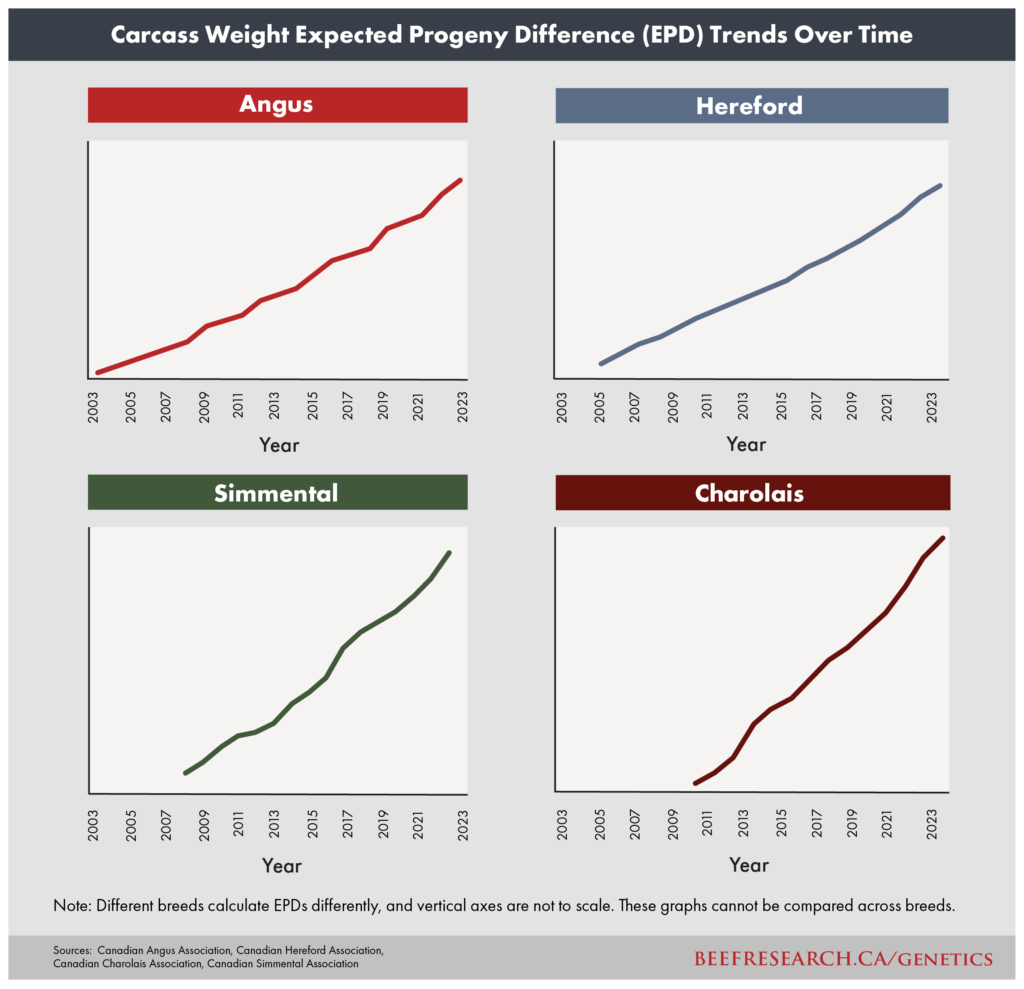

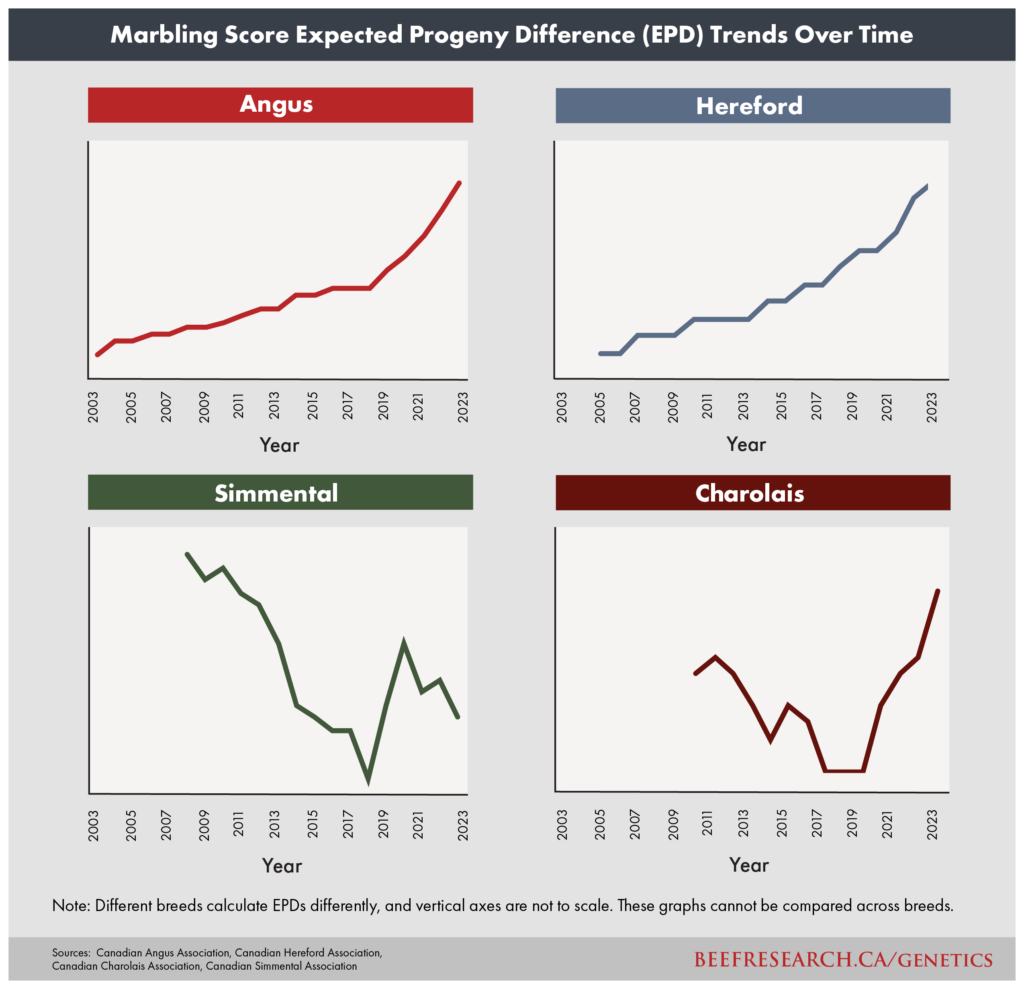

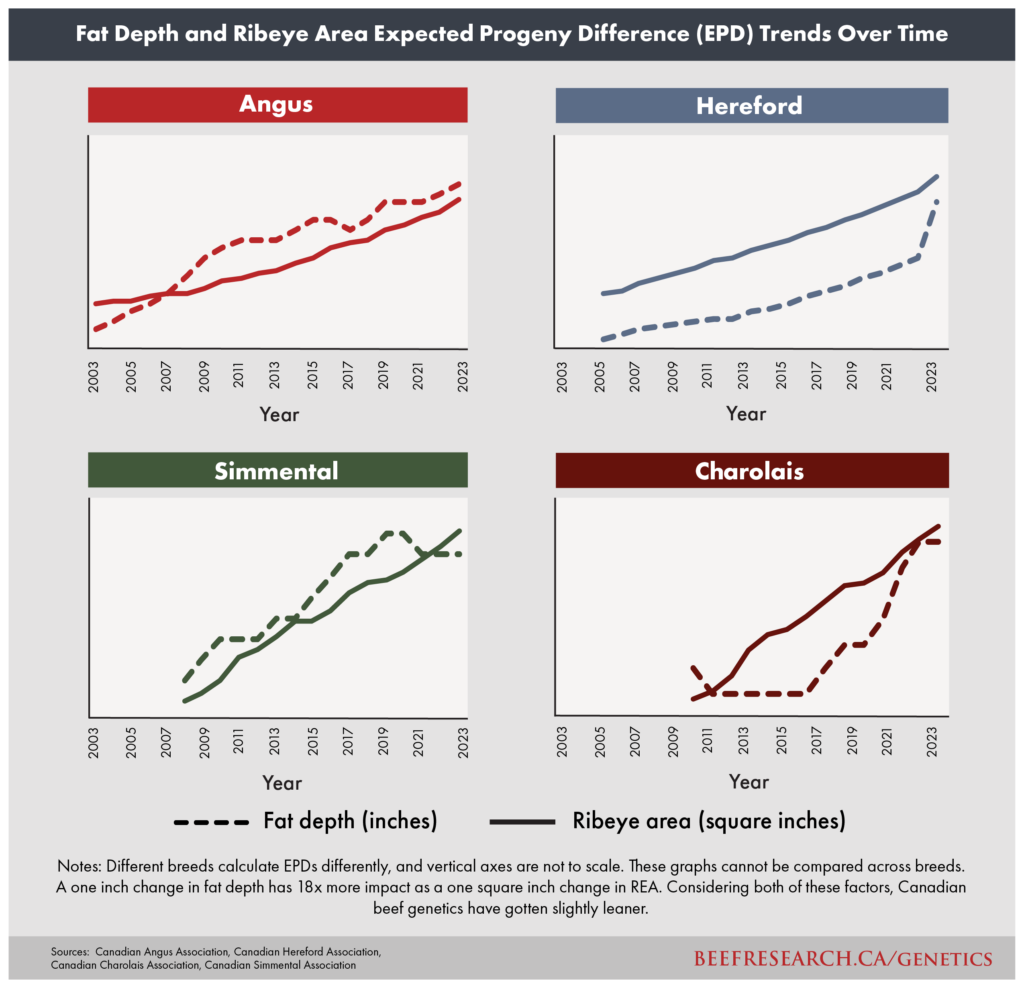

But genetic improvement has played a role. Breed associations calculate “genetic trends.” A genetic trend estimates how much of the change in a trait (like carcass weight or marbling score) is due to genetics alone, once some very complicated math has been used to take environmental and management effects out of the equation. Genetic trends for carcass traits aren’t always (or only) based on actual carcass data; they often rely heavily on live animal measurements (e.g., yearling weight or ultrasound measurements). They aren’t the same as carcass measurements, but they’re very good predictors and are easier to collect in large numbers. But that also means they’re independent evidence – they’re based on a different data set than packer grading data. The important point is that the genetic trends for marbling and carcass weight in Canada’s purebred Charolais, Hereford, Simmental and Angus cattle mirror the changes seen in the grading data – they have also generally trended up over time.

Bottom Line: Cattle can’t grow or marble if they don’t have the genetic potential to do so. Genetic selection for improved growth and marbling has allowed Canada’s beef industry to produce higher quality beef, more efficiently.

So what does this mean… to you? You might not have intended to buy genetics with improved growth or carcass quality. But if your breeder has been selecting for them, you’ve gotten them as part of the package (and so have your feedlot customers). We’ll revisit these opportunities in a future column.

The Beef Cattle Research Council is a not-for-profit industry organization funded by the Canadian Beef Cattle Check-Off. The BCRC partners with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, provincial beef industry groups and governments to advance research and technology transfer supporting the Canadian beef industry’s vision to be recognized as a preferred supplier of healthy, high-quality beef, cattle, and genetics. Learn more about the BCRC at www.beefresearch.ca.

Click here to subscribe to the BCRC Blog and receive email notifications when new content is posted.

The sharing or reprinting of BCRC Blog articles is typically welcome and encouraged, however this article requires permission of the original publisher.

We welcome your questions, comments and suggestions. Contact us directly or generate public discussion by posting your thoughts below.